The Invisible Prison of Perception: Why Donald Hoffman’s Radical Claim Reshapes Our World?

Donald Hoffman challenges the bedrock of our understanding: that reality is objective and our senses accurately perceive it. Dive into his Interface Theory of Perception, Conscious Realism, and the revolutionary idea that our world is a survival-driven user interface. Explore the profound philosophical, scientific, and practical implications of this claim for consciousness, AI, and the very nature of existence. This deep guide will push you to question everything you thought you knew.

The Unsettling Question of What We See

We walk through a world we instinctively believe to be objective, solid, and undeniably ‘real.’ We trust our senses implicitly, assuming they provide a faithful window onto an external reality that exists independently of us. This bedrock assumption underpins not just our daily lives, but centuries of scientific and philosophical thought. Yet, what if this fundamental belief is the grandest illusion of all?

Cognitive scientist Donald Hoffman posits a truly radical claim: our perceptions are not direct representations of an objective external world. Instead, they are intricate illusions, a kind of ‘user interface’ meticulously crafted by our consciousness, not to show us truth, but to guide us toward survival and reproductive success. This isn’t just an academic debate; it’s an urgent reframing of our place in existence, hinting at an invisible architecture that dictates our experience, and potentially, our destiny.

I invite you to step beyond the comfortable illusion and grapple with what this means. If our reality is merely an interface, then its fundamental structures, from space and time to physical objects themselves, become fluid, emergent properties of consciousness. This challenges the very foundations of scientific materialism and compels us to re-evaluate our deepest understanding of existence, knowledge, and purpose.

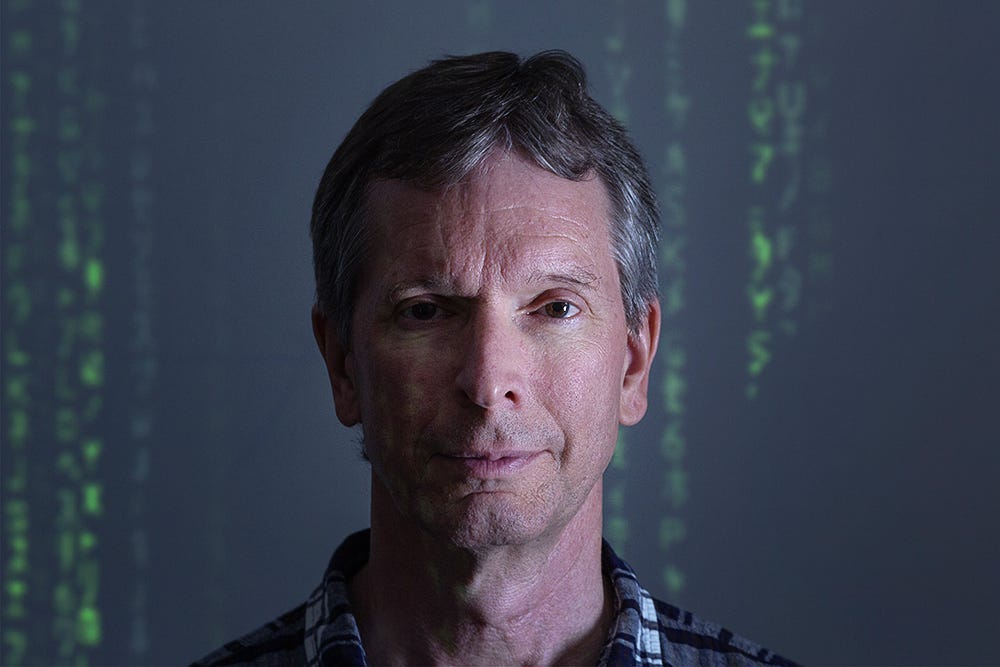

The Architect of Illusion: Donald Hoffman’s Interface Theory

At the heart of Hoffman’s revolutionary thesis lies the Interface Theory of Perception (ITP). Imagine your computer screen: you see icons, folders, and windows. These are not the actual electrical signals, microchips, or complex code beneath. They are a simplified, user-friendly interface designed to help you interact with the computer effectively, without needing to understand its underlying, infinitely complex reality.

Hoffman argues that our perceptions operate in precisely the same way. The vibrant apple you see, the solid chair you sit on, the expansive room you inhabit—these are merely ‘icons’ in your mind’s desktop interface. They do not accurately represent objective reality; rather, they provide ‘fitness-relevant information’ vital for survival and reproduction. Our sensory systems, shaped by natural selection, evolved to help us navigate the world efficiently, not to reveal its true, unvarnished nature. This explains why different species perceive the world in vastly different ways, each tailored to their specific survival needs.

Donald Hoffman: “Evolution has sculpted our perceptions not to see truth, but to survive. We see what we need to see to stay alive, not what is actually there.”

– Donald Hoffman, “The Case Against Reality”

Expanding on ITP, Hoffman introduces “conscious agents” as the fundamental building blocks of reality. These are not physical particles but rather subjective units capable of perception, decision, and action, interacting in a vast network. This leads to “Conscious Realism,” which posits that consciousness, not matter, is the primary substance of existence. What we perceive as the physical world is, in this view, a network of interconnected conscious experiences. This is a profound departure from the conventional materialist view and revitalizes philosophical idealism in a scientific context.

Echoes of Ancient Skepticism: Plato’s Cave to Modern Interfaces

While Hoffman’s claims feel startlingly modern, the fundamental question of whether our perceptions reflect reality is as old as philosophy itself. We can trace its lineage back to Plato’s timeless Allegory of the Cave. In this allegory, prisoners chained in a cave mistake shadows cast by unseen objects for reality. Only by escaping the cave and facing the sun can one apprehend true forms, a metaphor for philosophical enlightenment.

Centuries later, René Descartes grappled with the ‘evil demon’ hypothesis, questioning whether a powerful deceiver could be manipulating all his sensory experiences, rendering his perceived reality entirely false. George Berkeley proposed idealism, famously stating esse est percipi – “to be is to be perceived” – arguing that material objects cannot exist independently of being perceived by a mind. Immanuel Kant, in turn, distinguished between the ‘noumenal’ world (reality as it is, unknowable to us) and the ‘phenomenal’ world (reality as it appears to us, structured by our minds).

Hoffman’s work resonates deeply with these historical giants. He offers a contemporary, scientifically informed framework for what these thinkers intuited: that our direct experience of the world is inherently subjective and mediated. The interface theory provides an evolutionary explanation for why our ‘cave’ might be designed the way it is, and why our ‘shadows’ are so compellingly real to us. This continuity demonstrates that the radical questioning of reality is not a fleeting trend, but a perennial and vital human inquiry.

The Survival Game: Why Evolution Hides True Reality

The core of Hoffman’s evolutionary argument is strikingly counterintuitive: natural selection does not favor accurate perception. If seeing reality as it truly is required immense cognitive resources, and a simplified interface achieved the same or better survival outcomes with less effort, then evolution would inevitably opt for the interface. Think of it this way: knowing the precise atomic structure of a predator’s teeth is far less useful than simply perceiving “danger!” and reacting quickly. The brain, a highly efficient organ, optimizes for action, not for truth in an abstract, objective sense.