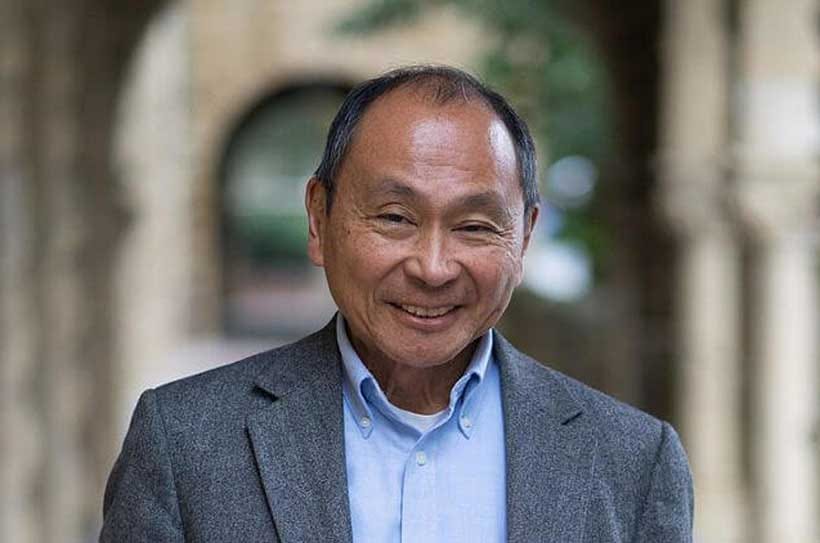

The Hangover at the End of History

Why Francis Fukuyama’s Prophecy Left Us Trapped in a Meaningless Present?

“The Hangover at the End of History: Why Francis Fukuyama’s Prophecy Left Us Trapped in a Meaningless Present” explores the implications and critiques surrounding Francis Fukuyama’s famous thesis presented in his 1992 work, “The End of History and the Last Man.” Fukuyama argues that the conclusion of the Cold War marked the definitive triumph of Western liberal democracy, positing it as the ultimate form of governance and signaling the cessation of ideological evolution.

However, the book has sparked considerable debate and criticism, particularly as contemporary geopolitical landscapes have revealed a resurgence of authoritarianism, populism, and societal discontent, undermining the optimistic vision Fukuyama proposed. Critics contend that it oversimplifies the complexities of global politics and ignores the multifaceted nature of historical development.

The financial crisis of 2008, the rise of nativist sentiments, and increasing geopolitical tensions highlight the fragility of democracies and the inadequacy of Fukuyama’s assertions regarding the permanence of liberal democracy. Scholars have pointed out that Fukuyama’s “Last Man Thesis,” which suggests a post-historical era of complacency, fails to account for the continued human longing for recognition, purpose, and societal meaning, potentially leading to new forms of conflict and competition in an ostensibly stable world.

The greatest danger for most of us is not that our aim is too high and we miss it, but that it is too low and we reach it.

Michelangelo

The book not only critiques Fukuyama’s initial claims but also engages with broader philosophical discourses, drawing comparisons with notable works such as Samuel Huntington’s “Clash of Civilizations” and Hegel’s dialectical framework. These discussions highlight the enduring complexities of historical narratives and the ongoing ideological struggles that challenge the notion of an “end of history.”

Overall, “The Hangover at the End of History” serves as a critical reflection on Fukuyama’s prophecy, arguing that rather than signaling a final resolution of historical conflicts, the present moment may embody a challenging intersection of past ideologies and contemporary dilemmas, leading to a society grappling with meaning in a seemingly stagnant era.

Historical Context

The concept of the “end of history,” popularized by Francis Fukuyama in his 1992 work, emerges against a backdrop of significant geopolitical shifts following the Cold War. Fukuyama posits that the end of the ideological struggle between capitalism and communism heralded the triumph of Western liberal democracy as the final form of government, thus marking a cessation of humanity’s ideological evolution.

This perspective aligns with the post-1989 optimism prevalent in the West, where the fall of the Berlin Wall symbolized a definitive victory for democratic values over authoritarian regimes. However, the historical context is more complex. The financial crisis of 2008, for instance, revealed deeper vulnerabilities within established democracies, highlighting economic stagnation and insecurity faced by the working and middle classes.

This discontent has made segments of the electorate in the U.S. and Europe susceptible to nativist and populist sentiments, challenging the notion of a stable, progressive political landscape as envisioned by Fukuyama. Increasing globalization and migration pressures, particularly from conflict regions, further complicated this scenario, provoking a backlash against liberal policies and contributing to the rise of illiberal alternatives.

Moreover, Fukuyama’s “Last Man Thesis“ raises critical questions about human motivation and societal evolution in a post-historical context. As basic needs are met in prosperous liberal democracies, the yearning for recognition and a meaningful existence may lead to societal discontent, contradicting the harmonious vision Fukuyama portrays. This paradox suggests that the end of history might not equate to the end of conflict or ideological struggle; rather, it may be a precursor to new forms of competition and societal challenges, necessitating a reevaluation of Fukuyama’s thesis in light of contemporary realities.

Ultimately, while Fukuyama’s thesis offered a framework for understanding the post-Cold War era, the resurgence of authoritarianism and polarization in democracies today raises profound questions about the validity and applicability of his ideas in our current historical moment.

Critical Reception

Francis Fukuyama’s “The End of History?” sparked significant debate upon its publication in the Summer 1989 issue of The National Interest. The article was met with a range of passionate responses, including contributions from notable intellectuals such as Allan Bloom, Irving Kristol, Gertrude Himmelfarb, Samuel P. Huntington, and Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who all commented in the same publication. Fukuyama’s thesis, which posited that liberal democracy might signal the endpoint of humanity’s sociocultural evolution, garnered both acclaim and criticism, making it a focal point in political discourse across the globe.

Despite its initial popularity, Fukuyama’s arguments were met with skepticism from various quarters. Critics contended that he oversimplified the complexities of history by suggesting a linear progression toward