The Great Refusal: Why Toynbee’s Cycle of Decline Illuminates Our Present Crisis?

Arnold J. Toynbee meticulously charted the rise and fall of civilizations, identifying a crucial hinge point: the ‘Challenge and Response’. Today, as the West faces unprecedented crises, Toynbee’s forgotten theory offers a chilling mirror, suggesting we are not merely struggling, but actively refusing the imperative to adapt and evolve. This is not about external threats alone, but an internal decay, a collective surrender to the comforts of decline.

The Echo of Empires: A Civilizational Foreboding

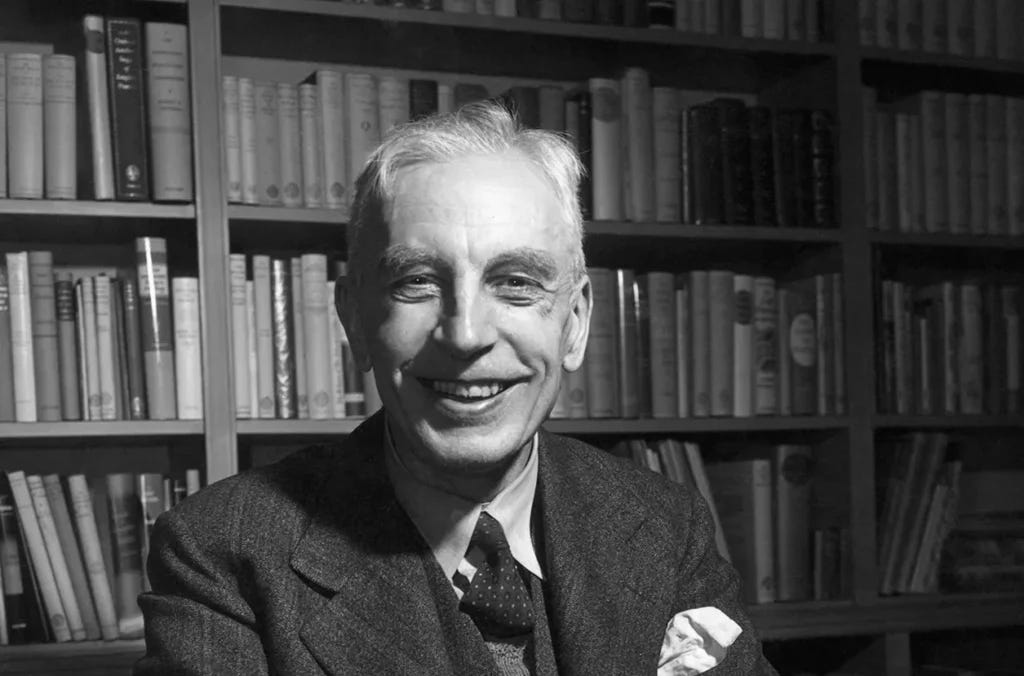

In the vast sweep of human history, empires rise and fall with an almost geological inevitability. Yet, what if their demise is not merely the outcome of external forces or random catastrophe, but a profound, internal choice? This unsettling question lies at the heart of Arnold J. Toynbee’s monumental work, “A Study of History”. Toynbee, a titan among 20th-century historians, didn’t just document the past; he sought to uncover the recurring patterns, the very grammar of civilizational life and death.

His central thesis, often overlooked in our era of short-term thinking, posits that civilizations thrive on a dynamic of “Challenge and Response.” A society encounters a formidable obstacle—environmental, social, or spiritual—and its capacity to offer a creative, adaptive response determines its fate. The West, in its current epoch, finds itself confronting a cascade of such challenges: ecological collapse, profound social fragmentation, escalating political polarization, and a deepening crisis of meaning. Yet, the responses we witness often feel inadequate, fragmented, or even a deliberate turning away. This isn’t merely a struggle for survival; it is, frighteningly, beginning to resemble a great refusal to live.

I find myself constantly returning to Toynbee’s insights because they cut through the superficiality of daily news cycles, offering a timeless lens through which to view our contemporary anxieties. He suggests that the true tragedy isn’t when a civilization is destroyed by an external enemy, but when it commits suicide from within, by failing its moral and intellectual duties. This guide is an exploration of that grim prophecy, and a look at whether the West is, in fact, choosing its own demise.

Toynbee’s Unsettling Vision: Challenge, Response, and Decay

To grasp the gravity of our situation through Toynbee’s eyes, we must first understand his core framework. Civilizations, for Toynbee, are not static entities but dynamic organisms that emerge, grow, break down, and ultimately disintegrate. This cycle is driven by the interaction of “Challenge and Response.” A successful response to a challenge allows a civilization to grow; a repeated failure leads to stagnation and decline.

“Growth is achieved when an individual or a society is able to respond to a challenge effectively, and thereby to surmount it, in such a way as to gain greater command over the environment, or over itself, than it had before.”

– Arnold J. Toynbee

Crucially, the nature of the response matters immensely. A truly creative response comes from a “Creative Minority” – individuals who possess vision, moral courage, and the ability to inspire the wider society to adapt. As a civilization matures and begins to break down, this creative minority often gives way to a “Dominant Minority.” This new elite maintains its position through force or convention, no longer inspiring but merely asserting control. Their responses become rigid, imitative, or self-serving, failing to address the underlying challenges effectively.

Below the dominant minority is the “Internal Proletariat” – a mass of people who have lost faith in the leadership and the existing social order, feeling alienated and dispossessed. Then there’s the “External Proletariat,” often barbarian tribes or neighboring peoples who are drawn to, yet excluded from, the failing civilization, eventually contributing to its downfall. This complex interplay of internal and external dynamics, leadership and disillusionment, defines the arc of civilizational history in Toynbee’s schema. It’s a sobering thought, isn’t it? That the seeds of decay are often sown not by invaders, but by a failure of internal will and vision.

The West’s Gauntlet: Unprecedented Crises, Familiar Failures

Let us now apply Toynbee’s magnifying glass to our own era. The West today faces an array of challenges arguably more complex and interconnected than any in recorded history. Consider the accelerating ecological crisis: climate change, biodiversity loss, resource depletion. These are not merely scientific problems; they are moral and systemic ones, demanding radical shifts in our consumption, production, and fundamental worldview. Yet, our collective response is marked by political paralysis, economic short-termism, and a widespread, almost willful, denial.

Internally, social fragmentation has reached alarming levels. Political polarization is not just about policy disagreements but fundamental disputes over reality, truth, and shared values. Economic inequality strains the social fabric, breeding resentment and disillusionment. Technological disruption, while offering immense potential, also threatens to reshape human experience in ways we barely understand, from the erosion of privacy to the algorithmic manipulation of public discourse. We are witnessing an unraveling of consensus, a fracturing of the public square, and a decline in institutional trust.

I see in these patterns the very failures Toynbee described. The challenges are clear, yet our responses often seem to fall into the categories of the “Dominant Minority” – maintaining the status quo, deflecting responsibility, or offering superficial solutions that avoid systemic change. There’s a palpable sense that the institutions and leaders who should be guiding us through these storms are instead paralyzed by self-interest, ideological rigidity, or simply a lack of genuine creative vision. The collective comfort we derive from denial is proving to be a more formidable adversary than any external threat.

Dominant Minorities and the Lure of Stasis

When a civilization enters its breakdown phase, Toynbee observed a critical shift: the “Creative Minority” responsible for its initial growth gives way to a “Dominant Minority.” These are elites who cling to power through coercion, propaganda, and the sheer inertia of tradition, rather than inspiring genuine progress. Their hallmark is an inability to innovate or adapt; they repeat past successful formulas even when the challenges demand entirely new approaches. Think of the endless cycles of political bickering, the corporate pursuit of quarterly profits over long-term sustainability, or the intellectual paralysis in our institutions of higher learning.

We see this play out in our political landscape, where leaders often prioritize retaining power over tackling existential threats. We see it in economic systems that reward speculation and extraction over genuine value creation and equitable distribution. And we see it in the media, where complex issues are reduced to simplistic narratives that reinforce existing biases, rather than fostering critical thought. The dominant minority, in Toynbee’s view, often perpetuates a false sense of security or progress, masking the underlying rot with spectacle and distraction. They prefer the illusion of control to the painful reality of necessary transformation.

This is where the universal human weakness of conformity and comfort comes into play. The dominant minority succeeds because many of us, the broader population, are complicit in our passivity. We are lulled by consumerism, distracted by digital entertainment, and intimidated by the complexity of the issues, allowing those in power to maintain a stifling status quo. It’s a mirror effect: we recognize the failings of leadership, yet our own reluctance to demand profound change reflects a deeper societal malaise.

The Internal Proletariat’s Unrest: A Spiritual Alienation

A critical symptom of civilizational breakdown, according to Toynbee, is the emergence and growth of an “Internal Proletariat.” These are not necessarily the economically poor, but rather all those within the society who feel alienated from its dominant institutions, values, and narrative. They no longer feel a sense of belonging or shared purpose; they are “in the society but not of it.” This spiritual alienation is profound, leading to cynicism, resentment, and a search for alternative forms of meaning and community outside the established order.

“The distinguishing mark of the Internal Proletariat is that it feels ‘no longer at home’ in the society which is nominally its own, but which has come to be regarded as its oppressor.”

– Arnold J. Toynbee

Do we not see this burgeoning “Internal Proletariat” all around us? From the disaffected youth increasingly turning to radical ideologies, to the widespread distrust in media, government, and even scientific institutions. People are searching for meaning, belonging, and justice in a world that often feels arbitrary, unjust, and spiritually empty. This search can manifest in many forms: new religious movements, intense political tribalism, or a retreat into niche online communities. The common thread is a profound disillusionment with the existing order and a desperate yearning for something more authentic and binding.

This alienation is an existential threat to any civilization, because it erodes the collective will to act. When a significant portion of the population feels disconnected and unrepresented, it becomes impossible to forge a unified response to the challenges at hand. This is not just a political problem; it is a crisis of the soul, a deep spiritual sickness that saps the vitality and coherence of the entire civilization.

From Universal States to Spiritual Escapism: Toynbee’s Final Warnings

As a civilization spirals deeper into breakdown, Toynbee observed that it often attempts to preserve its failing structure by forming a “Universal State.” This is a desperate, often imperialistic, effort to impose a rigid political and administrative unity over a vast area, stemming the tide of internal and external pressures. Such states are not signs of strength, but rather of a civilization’s terminal illness, a futile attempt to arrest a disintegration that has already taken root. In our modern context, we might see parallels in the push for global governance without genuine popular consent, or the increasing homogenization of culture under the guise of unity.

The universal state eventually crumbles, but its spiritual legacy often gives rise to a “Universal Church” – a new spiritual force or ideology that provides meaning and community for the alienated “Internal Proletariat.” This ‘church’ can be a genuine wellspring of renewed spiritual life, potentially laying the groundwork for a new civilization, or it can be a form of escapism, offering solace without truly addressing the deeper issues. Today, we might observe the rise of various globalist ideologies, environmental movements, or even digital communities as nascent forms of these ‘universal churches,’ attempting to fill the void left by decaying traditional institutions.

Toynbee’s warnings here are particularly resonant. Are we, in the West, witnessing the last gasp of a “Universal State” attempting to impose order through technocratic solutions and globalized systems, while a myriad of “Universal Churches” – from fundamentalist revivals to digital utopias – vie for the allegiance of the disillusioned? The apocalyptic framing becomes undeniable: we are at a juncture where the choices made, or refused, will determine not just the next decade, but the fate of a civilizational epoch. The question is whether these new spiritual currents will be truly creative or merely another form of comfortable denial.

Forging a New Response: The Imperative of Conscious Action

If the West is indeed caught in Toynbee’s cycle of decline, what then is the path forward? For Toynbee, the breakdown is not an absolute end, but a call to transformation. The key lies in the re-emergence of a “Creative Minority” – individuals and groups who refuse to succumb to the dominant minority’s inertia and the proletariat’s despair. This is where intellectual depth must meet emotional fire, where critical analysis fuels courageous action.

Such a creative minority must first confront the universal human weakness of denial head-on. It requires an honest appraisal of our challenges, free from ideological blinders or the pursuit of ephemeral comforts. It means fostering genuine intellectual rigor, a commitment to truth over convenience, and a willingness to engage in the difficult work of self-critique. This is not about retreating into cynicism but about rebuilding from the ground up, starting with individual responsibility and expanding outward.

Practically, this could mean:

Cultivating Local Resilience: Reinvesting in local communities, economies, and social bonds to mitigate the fragility of global systems.

Prioritizing Meaning over Materialism: Shifting societal values away from endless consumption towards genuine human flourishing, spiritual depth, and purpose.

Reclaiming Education: Fostering critical thinking, historical literacy, and moral reasoning, rather than merely vocational training or ideological indoctrination.

Ethical Technological Development: Demanding that technology serves human well-being and freedom, rather than becoming a tool for control or distraction.

Embracing Moral Courage: Speaking truth to power, challenging dominant narratives, and taking personal risks for the sake of ethical principles.

The stakes are existential. This is about reclaiming our agency, not as passive consumers of culture or ideology, but as active participants in shaping our collective destiny. It’s a call to be present, to respond authentically, and to choose growth over decay, even when that choice is painful and unpopular.

The Unfolding Narrative: Choosing Decline or Rebirth

Arnold Toynbee’s “A Study of History” is not merely a chronicle of past failures; it is a prophetic mirror held up to our present. It reminds us that civilizations are not static monuments but living processes, constantly tested by new challenges. The current crisis of the West, therefore, is not an external imposition but an internal trial, a moment of profound choice. We are witnessing, in real-time, the unfolding narrative of our own civilization’s response—or lack thereof—to its ultimate tests.

The dialectic is clear: the immense challenges (thesis) are met with a pervasive failure of creative response (antithesis), driven by dominant minorities and a spiritually alienated proletariat. The synthesis, should it emerge, requires a conscious, courageous act of will from individuals and groups who refuse to accept the current trajectory. This is a timeless truth that illuminates our timely fractures: misinformation, authoritarian tendencies, technological overreach, and cultural drift.

Ultimately, Toynbee’s work challenges us to look beyond the immediate headlines and recognize the deeper currents of history at play. It compels us to ask: Are we, as a civilization, truly prepared to confront our challenges with creativity and moral conviction, or will we continue on the path of “the great refusal,” choosing the comfortable slide into decline? The answer, I believe, lies within each of us, in our willingness to engage with the urgent, existential stakes of our time, and to act as if the future of civilization depends on it – because it very well might.

We’re on the path of least resistance, too distracted and addicted to our comforts and routines. Many of us see the reality but lack the means to change it. Even our elected representatives, those not of the GOP, don’t seem able to rein this lawlessness. For months we keep asking, what can we do? The only answer has been, peaceful protest, which they now try to deny us. The truth is, this regime cares nothing about the Constitution, the country, or the people. The GOP has abandoned us and the Democrats are too weak to lead. It’s going to take something far more radical than anything we’ve seen so far, and so much damage has been done to the country already it’s going to be a hard recovery if we manage to turn it around. The sooner we start the better.

The point of this article is not that some political party can come to our rescue and “rejuvenate”‘the Constitution. The problem is much deeper. Sense of purpose and meaning are the outgrowth of a cohesive society, not a fragmented one. This is, at base, a cultural/philosophical problem, not curable by a minority of citizens on the “right path”. It is correct that the majority is diverted by material comforts and entertainment. I fear this era will just have to run its course.