The Girardian Trap: Why Our Secret Envy Is Fueling Society’s Collapse

We live in an age of unprecedented connection, yet also one of escalating conflict and anxiety. This article delves into René Girard’s profound theory of mimetic desire to uncover the ancient, invisible force driving our relentless pursuit of what others have, and how this dynamic has been dangerously amplified by social media. Understand how this ‘Girardian Trap’ is eroding personal well-being and threatening the very foundations of our civilization, and discover paths to break free from its grip.

The Silent Epidemic of Imitation

I want to begin with a confession: much of what I once thought were my own deeply held aspirations were, in fact, borrowed. Not consciously, of course. Nobody wakes up thinking, “I’m going to desire exactly what my neighbor desires today.” Yet, if we are honest, a significant portion of our wants—from the career paths we pursue to the lifestyles we envy—are shaped by the people around us. This isn’t a flaw of character; it’s a fundamental aspect of being human, a phenomenon the brilliant French thinker René Girard termed mimetic desire.

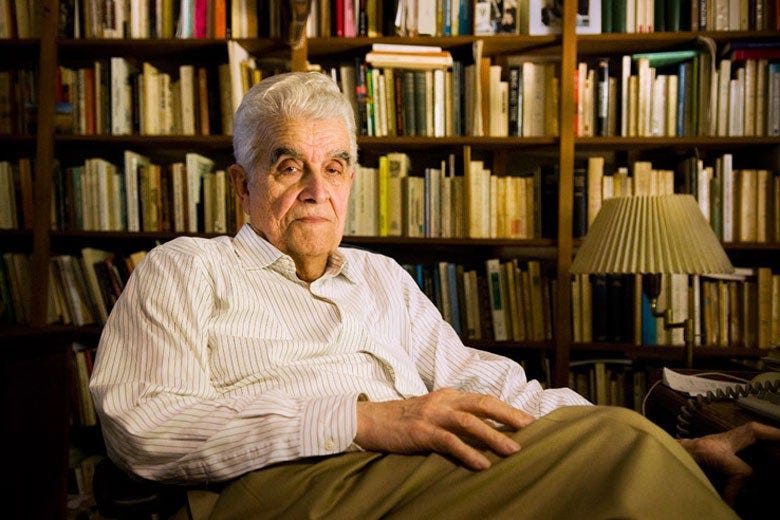

Girard, often overlooked in mainstream discourse, offered a lens through which to understand the true drivers of human behavior, conflict, and culture. His work illuminates an uncomfortable truth: our desires are not autonomous; they are imitative. We see something desired by another, and suddenly, it becomes desirable to us. This isn’t merely benign emulation; it’s the invisible spark that ignites rivalry, resentment, and ultimately, societal breakdown. In an age dominated by the incessant comparisons fostered by social media, this ancient mechanism has been weaponized, transforming our collective human weakness into an engine of division. I believe we are caught in a ‘Girardian Trap,’ and understanding its mechanics is the first step toward finding our way out.

What Is Mimetic Desire? The Engine of Our Longing

To grasp the ‘Girardian Trap,’ we must first understand its central concept: mimetic desire. Unlike traditional psychological views that often posit desires as originating from an individual’s internal needs or objective qualities of an object, Girard argued for an ‘interdividual’ understanding of desire. Put simply, we desire because someone else desires. A ‘model’ or ‘mediator’ shows us what is desirable, and we, as imitators, follow suit.

Man is the creature who does not know what to desire, and he turns to others to make up his mind. We desire what others desire because we imitate their desires.

– René Girard

This isn’t just about consumerism, though it clearly fuels our purchasing habits. It’s deeper. We imitate not only the desire for objects but also for status, identity, recognition, and even suffering. Consider children: they learn by imitation, often desiring the same toy as their playmate, not because of the toy’s inherent qualities, but because it is desired by the other. This dynamic doesn’t disappear in adulthood; it simply becomes more sophisticated and often, more insidious.

The critical distinction Girard made is between ‘external mediation’ and ‘internal mediation.’ In external mediation, the model is far removed from the imitator (e.g., desiring to be like a historical figure or a distant celebrity). The model doesn’t compete for the same object, and rivalry is minimal. However, in ‘internal mediation,’ the model is close—a friend, a colleague, a contemporary influencer. Here, the imitator and the model desire the same object, leading to direct rivalry. The model becomes an obstacle, and the relationship can devolve into antagonism, where the original object of desire becomes secondary to the rivalry itself.

From Desire to Rivalry: The Escalation of Mimetic Conflict

Once mimetic desire shifts from external to internal mediation, the seeds of conflict are sown. When two or more individuals desire the same thing because they are imitating each other’s desires, they inevitably become rivals. The object itself often loses its original appeal; what matters is depriving the rival of it. This isn’t rational competition; it’s a deep-seated, often unconscious, struggle for recognition and dominance mediated through shared desire.

Girard argued that this mimetic rivalry is the ultimate source of all human conflict, from petty disagreements between friends to large-scale societal violence. As the rivalry intensifies, the distinction between the rivals blurs. They become mirror images of each other, each obsessed with the other’s actions and desires, caught in a feedback loop of escalating aggression. This is why wars often become so brutal: the original grievance fades, replaced by a consuming desire to destroy the rival, who has become an existential threat to one’s own identity and desire.

I’ve observed this dynamic play out countless times in our current political and cultural landscape. Opposing factions become so consumed with what the ‘other side’ desires or fears that their own principles become secondary to the mimetic rivalry itself. Each side models a hostile desire towards the other, escalating a conflict where victory becomes less about ideals and more about the symbolic defeat of the rival. The blurring of distinction between rivals in a mimetic crisis is a terrifying precursor to generalized violence and societal breakdown.

The Scapegoat Mechanism: Society’s Ancient Solution

If mimetic rivalry is such an inherent force, how have societies survived? Girard proposed the concept of the ‘scapegoat mechanism.’ When mimetic rivalries reach a critical point, threatening to tear society apart in a ‘crisis of indiscrimination’ (where everyone is a rival to everyone else), an unconscious, spontaneous act often occurs: the collective channeling of all violence and blame onto a single, arbitrary victim—the scapegoat.

This victim, often someone marginalized or an outsider, is suddenly perceived as the cause of all discord. The community, unified in its hatred and violence against this single individual, momentarily restores peace and order. The scapegoat’s expulsion or death purges the collective violence, and the community experiences a profound sense of catharsis and renewed unity. This mechanism, Girard argued, is the foundation of archaic religion and the origin of many myths and rituals, which often disguise the arbitrary nature of the victim and sanctify the violence.

What we want is not always what we say we want. What we need is often hidden beneath layers of cultural programming and mimetic influence.

– Esther Perel

The tragedy, of course, is that the scapegoat is innocent. The mechanism works because it conceals the truth of mimetic desire, allowing societies to repeatedly resolve their internal conflicts without ever addressing the root cause. While overt ritualistic scapegoating has largely diminished in modern societies, the psychological impulse remains. We still see this impulse in cancel culture, political vilification, and the search for external enemies, where a collective emotional frenzy can converge on an individual or group, deflecting deeper societal anxieties.

The Digital Amplification: Social Media as the Mimetic Machine

If Girard were alive today, I believe he would see social media as the ultimate mimetic machine. Never before have we had such ubiquitous, constant exposure to the desires of others. Platforms like Instagram, X (formerly Twitter), and TikTok are built on internal mediation, placing models—influencers, friends, even strangers—directly into our daily lives, showcasing their curated lives, their ‘wins,’ their opinions, their objects of desire.

This constant stream of curated desires creates an unprecedented environment for mimetic contagion. Our feeds are not just sources of information; they are catalogs of desirable lives, bodies, possessions, and experiences. We scroll, we compare, and we often find ourselves desiring what others appear to have, fueling a silent epidemic of envy and inadequacy. The ‘fear of missing out’ (FOMO) is a perfect manifestation of mimetic desire: we fear not having what others are experiencing, because their experience has become the model for our own desirability.

Moreover, social media platforms, with their echo chambers and engagement algorithms, actively exacerbate mimetic rivalry. They connect individuals who share similar desires or grievances, allowing those desires to amplify within the group. When a common rival or enemy emerges (e.g., a political opponent, a perceived ‘other’), these platforms become highly efficient engines for collective scapegoating, consolidating a diffuse sense of grievance into a focused, often digital, mob. The anonymity and distance afforded by screens only serve to strip away the humanizing elements that might otherwise inhibit such destructive mimetic violence.

The Crisis of Distinction: When Everyone Desires the Same

The ultimate consequence of unbridled mimetic desire, particularly amplified by digital platforms, is a ‘crisis of distinction.’ In traditional societies, roles, hierarchies, and values often provided clear boundaries and distinct identities. While imperfect, these structures helped to channel mimetic desire, preventing it from spiraling into total chaos. In modern, hyper-connected, and increasingly secular societies, these distinctions are eroding. We are told we can be anything, have anything, and should strive for ‘the best’—which inevitably means what everyone else is also striving for.

When everyone desires the same few things—be it