The Digital Age's Memory Trap

How Dostoevsky Predicted Our Epistemic Crisis and Why It Matters

Dive deep into how the relentless information overload of the digital age is creating an 'epistemic crisis of memory,' eroding our personal truth and sense of self. This comprehensive guide, inspired by Dostoevsky's profound insights, reveals the hidden costs of outsourced memory and fragmented attention, offering practical strategies to reclaim your cognitive sovereignty and protect your inner world.

The Invisible Prison of Our Minds: An Introduction to Memory's Peril

We live in an era where information is not just abundant, but truly overwhelming. Every day, we navigate a deluge of data, news, opinions, and entertainment, all promising to enrich our understanding and expand our horizons. Yet, what if this constant, unfettered access to everything is, paradoxically, diminishing something vital within us? What if the very tools designed to extend our cognitive reach are, at a deeper level, eroding our capacity for genuine memory and, by extension, our personal sense of truth?

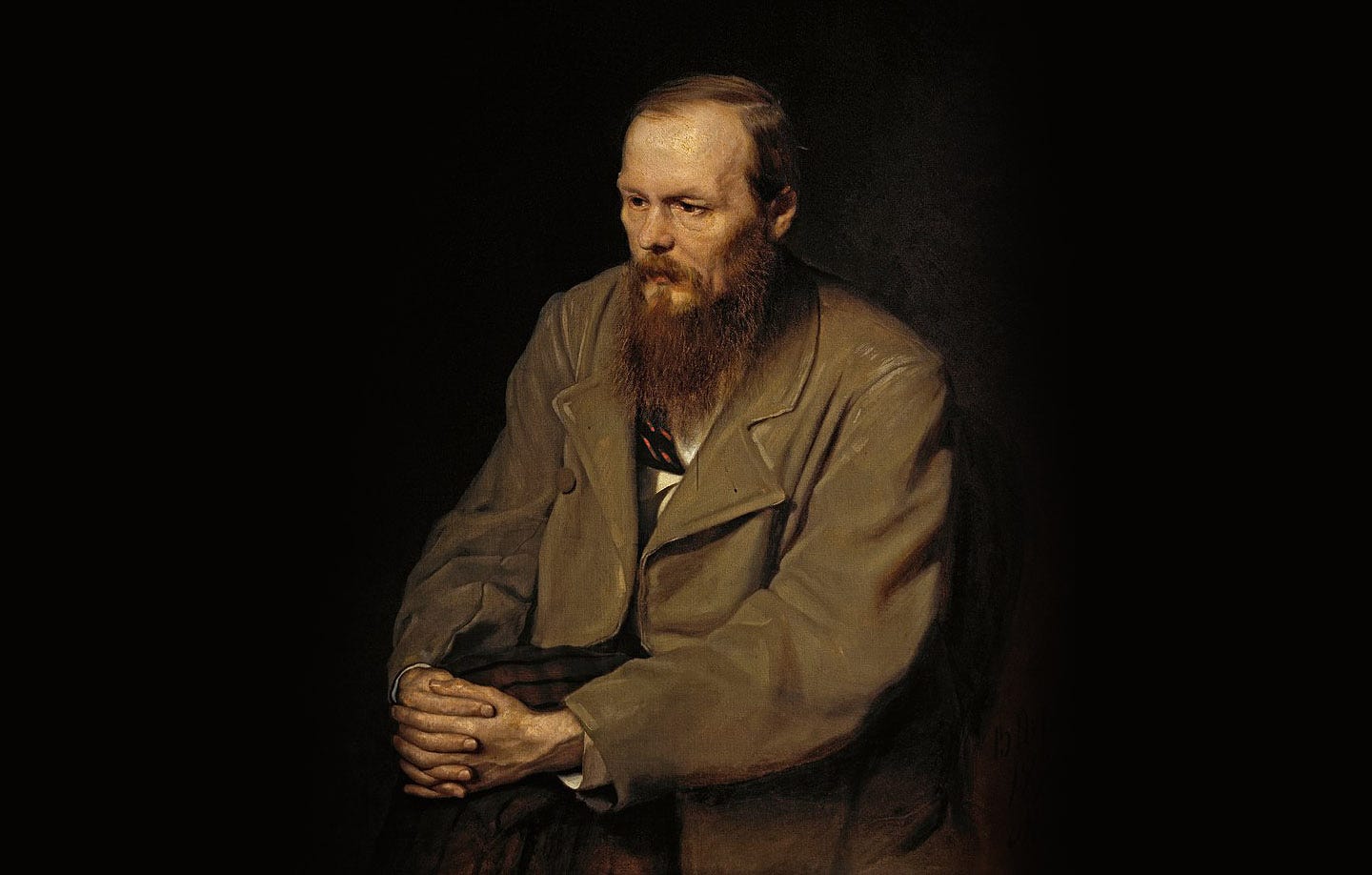

I believe we are witnessing a profound phenomenon: an epistemic crisis of memory in the digital age. This isn't merely a lament about shorter attention spans, though that is certainly a symptom. It's about a fundamental restructuring of how we perceive, process, and retain information, leading to a precarious instability in our individual and collective realities. In this deep guide, I want to take you on a journey through this crisis, illuminated by the surprising prescience of a literary titan who lived long before the internet: Fyodor Dostoevsky.

Dostoevsky's Premonition: The Burden of Hyper-Consciousness

Dostoevsky, the master of psychological depth, populated his novels with characters who were perpetually at war with themselves and their fragmented realities. Consider the Underground Man, tormented by an excessive, self-lacerating consciousness, drowning in his own thoughts and observations, yet unable to act or form a coherent identity. His suffering stems not from a lack of information, but from an inability to synthesize it, to forge a meaningful truth from the chaos of his inner world.

Dostoevsky's genius lies in his depiction of the modern individual’s struggle against the weight of self-awareness and external pressures. His characters often grapple with a feeling of being overwhelmed by too many possibilities, too many perspectives, leading to paralysis and an inability to anchor themselves in a stable truth. This is a crucial premonition for our time. His insights suggest that an overstimulated, fragmented mind, one constantly processing external stimuli without sufficient internal integration, can lead to a profound suffering and a loss of personal authenticity.

The more a man is conscious, the more he suffers.

– Fyodor Dostoevsky, Notes from Underground

This suffering, for Dostoevsky, was often a path to moral and spiritual awakening, but it began with an intensely felt fragmentation of the self. In our digital age, this fragmentation is not just internal; it's constantly fed and amplified by external forces.

The Digital Deluge: An Ocean of Data, A Desert of Attention

Today, our 'underground' is the digital realm – a place of endless feeds, notifications, and alerts. We are barraged by a constant stream of information, each snippet vying for our precious and increasingly scarce attention. This isn't just about passively consuming content; it's about actively participating in a feedback loop that trains our brains for superficial engagement rather than deep thought.

Think about your daily routine: checking emails, scrolling social media, switching between tabs, responding to messages. Each of these actions fragments our focus, pulling us in a dozen different directions simultaneously. Our attention span, once capable of sustained, linear engagement, is now conditioned to flit from one stimulus to the next, rarely lingering long enough to grasp the full implications of what we encounter. This relentless digital deluge is not merely a nuisance; it's actively reshaping our cognitive architecture, making deep concentration an increasingly rare and difficult feat.

We are drowning in information but starved for knowledge.

– John Naisbitt

Naisbitt's observation, made decades ago, feels even more pertinent now. We have more 'facts' at our fingertips than any generation before, but our ability to transform these facts into coherent, actionable knowledge, let alone deep wisdom, is severely compromised by the very medium through which they arrive.

The Outsourced Mind: When Memory Becomes an External Hard Drive

One of the most insidious effects of the digital age is the outsourcing of our memory. Why commit facts to memory when Google can recall them instantly? Why remember directions when a GPS can guide us? This convenience, while seemingly innocuous, carries a hidden cost. Our brains are incredibly adaptive, and when we offload cognitive tasks to external devices, those internal capacities begin to atrophy.

Memory is not just a filing cabinet for facts; it is the loom upon which we weave our personal narratives, our understanding of the world, and our very identity. When we rely on external sources to store and retrieve information, we weaken the neural pathways that construct and reinforce our internal world. We become less like a robust, self-sufficient intellect and more like a terminal connected to a vast, but external, database. This externalization makes us dependent, vulnerable, and less capable of independent thought, critical analysis, and original synthesis.

The act of remembering is a creative process, a reconstruction of the past filtered through our present understanding. If the raw material for this reconstruction is constantly shifting, easily edited, or stored externally without internal integration, what becomes of our ability to build a stable, personal truth?

The Fragile Self: The Erosion of Personal Truth

The erosion of memory inevitably leads to the fragmentation of the self. Our personal truth is intrinsically linked to our lived experiences, our memories, and our ability to draw connections between past and present. If these memories are constantly challenged by new information, conflicting narratives, or simply forgotten due to digital distraction, our sense of self becomes fragile and unstable.

Dostoevsky understood that a stable, coherent identity is built upon an internal consistency, however fraught. But in a world where personal histories can be instantly revised, where algorithms shape our perceived reality, and where a consistent narrative feels almost impossible to maintain, how do we know who we are? We become susceptible to external influences, less grounded in our convictions, and more prone to the psychological discomfort of an unmoored existence. This isn't just about forgetting where you put your keys; it's about losing the internal compass that guides your moral and philosophical journey.

Confronting the Epistemic Abyss: What Do We Truly Know?

The culmination of these trends – fragmented attention, outsourced memory, and eroded personal truth – is what I term the

Reclaiming Your Inner Citadel: Strategies for Cognitive Sovereignty

If Dostoevsky's warnings and our current predicament resonate deeply with you, the good news is that we are not entirely powerless. Reclaiming our cognitive sovereignty in the digital age requires intentionality and a conscious effort to rebuild the internal structures that are slowly being dismantled. Here are some strategies you can begin to implement:

Practice Digital Minimalism: Consciously reduce your digital consumption. Set specific times for checking emails and social media. Turn off notifications. Create 'digital-free zones' in your day or week to allow your mind to wander and connect internally.

Embrace Deep Work and Reading: Engage in activities that require sustained, focused attention. Read physical books, dedicate time to single tasks without interruption. This rebuilds your capacity for concentration.

Cultivate Internal Memory: Make a conscious effort to remember. Instead of immediately Googling a fact, try to recall it first. Journal regularly to consolidate your thoughts and experiences, transforming fleeting moments into integrated memories.

Engage in Synthesis, Not Just Consumption: Don't just absorb information; actively try to connect it, analyze it, and form your own conclusions. Discuss ideas with others, write summaries, and challenge your own assumptions. This is how information transforms into knowledge and wisdom.

Prioritize Analog Experiences: Spend time in nature, engage in face-to-face conversations, pursue hobbies that require physical and mental presence. These activities ground you in the present and foster a holistic sense of self, outside the digital echo chamber.

These practices are not about rejecting technology entirely, but about mastering it rather than being mastered by it. They are about creating space for your inner world to flourish, to rebuild the strength of your memory and, consequently, the resilience of your personal truth.

The Road Less Traveled: Final Thoughts on Memory and Truth

The epistemic crisis of memory in the digital age is a subtle yet profound challenge to our very humanity. Dostoevsky, in his profound explorations of the human psyche, offered us glimpses into the dangers of a mind unmoored, overwhelmed by its own capacity for thought without the grounding of genuine truth.

As we navigate an increasingly complex digital landscape, the call to cultivate our internal world, to guard our attention, and to nurture our memory has never been more urgent. It is an act of resistance against the forces that seek to fragment our selves and dilute our truths. By consciously choosing to engage deeply, to remember intentionally, and to synthesize thoughtfully, we can begin to reclaim not just our memory, but the very essence of who we are. Your truth, your memory, and your authentic self are worth fighting for.