The Council’s Fatal Architecture: How Including India Validates a Broken Design

France’s renewed support for India’s UNSC bid feels like progress, but a deeper diagnosis reveals it may be the final symptom of a dying order. We examine the pathology of 1945’s lingering ghost.

Symptoms: The Recurring Fever of Reform

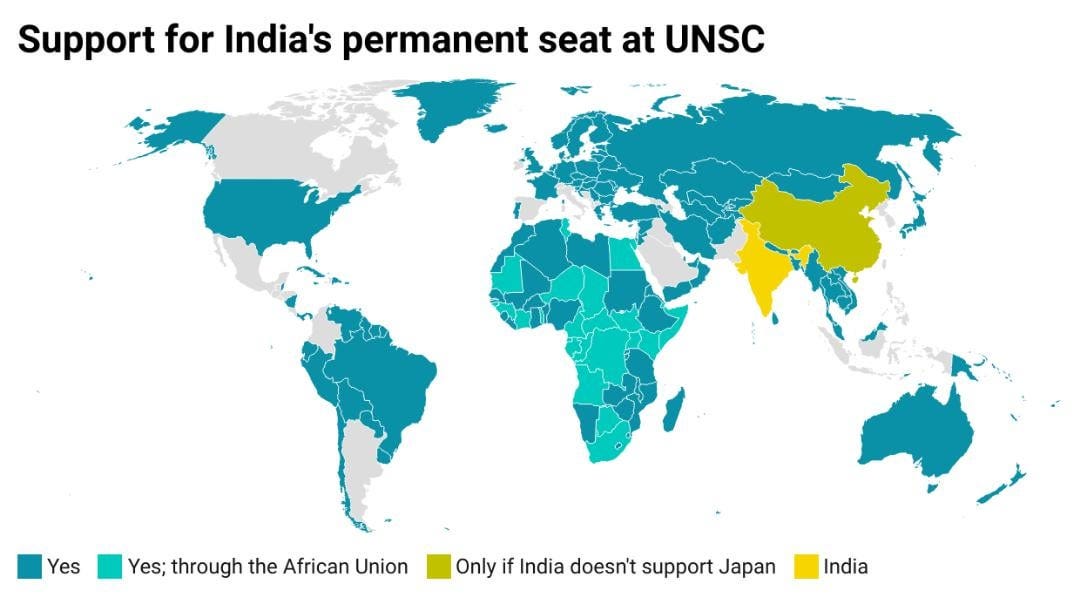

The cycle is almost ritualistic in its predictability. On November 19, 2025, France once again reaffirmed its support for India obtaining a permanent seat on the UN Security Council, complete with veto power. The announcement, bolstered by deepening defense ties and Rafale sales, was greeted with the usual diplomatic fanfare. We see the headlines, the handshakes, and the renewed hope that the geopolitical architecture of 1945 is finally bending toward the reality of the 21st century. It feels like movement. It looks like progress. But in medicine, a fever that returns at regular intervals is not a sign of healing; it is a sign of a chronic, underlying infection that the body—or in this case, the body politic—cannot shake.

We are witnessing a geopolitical pathology where the promise of inclusion serves to distract from the rot of the institution itself. The persistent clamor for seats—for India, for Brazil, for Africa—masks the uncomfortable reality that the table itself may be rotting. We treat the exclusion of these powers as the disease, assuming that if we simply administer the medicine of ‘membership,’ the patient will recover. But what if the exclusion is merely a symptom? What if the structure of the Security Council was never designed to accommodate a shifting world, but to freeze a specific moment of victory in amber? I watch these announcements not with hope, but with a sense of déjà vu, recognizing the pattern of a system that offers gestures of reform to avoid the surgery it actually needs.

Diagnosis: The Pathology of Static Power

The true diagnosis is not that the Security Council is under-represented; it is that it is suffering from institutional sclerosis. The organ created to maintain peace has calcified into a mechanism for preserving hierarchy. By focusing on who gets to sit in the big chairs, we inadvertently validate the existence of the chairs themselves. The veto power is not a tool of justice; it is a remnant of imperial privilege, a way for the victors of a war fought eighty years ago to dictate the terms of the future. When France supports India’s bid, it is not dismantling this hierarchy; it is inviting a new member into the oligarchy. It is an attempt to graft living tissue onto a necrotic limb.

This diagnosis reveals a darker truth about our international order: we are addicted to the illusion of control. We believe that if we can just get the ‘right’ countries in charge, the system will work. But as the philosopher Simone Weil observed regarding the nature of force and political machinery:

The official language of the state is always the language of justice, but the reality of the state is always the reality of force. To believe that we can reform the machine by changing its operators is the ultimate delusion.

– Simone Weil

The structural flaw is the concept of the ‘Great Power’ itself—the idea that a select few nations possess the moral weight to decide the fate of the many. We are trying to cure inequality by expanding the aristocracy, which is a contradiction in terms.

Prognosis: The Paralysis of the Expanded Table

If we leave this condition untreated—or worse, if we treat it with the placebo of expansion—the prognosis is grim. Let us play out the scenario where India, Brazil, and others are granted veto power. Does the United Nations become more effective? History and logic suggest the opposite. We will likely see a descent into total paralysis. The gridlock we see today between the US, Russia, and China will not be alleviated by adding more veto-wielding players; it will be multiplied. The council will become a dense web of competing national interests where action becomes a mathematical impossibility.

This leads to the eventual septic shock of the international system: irrelevance. When the ‘official’ body for global peace becomes incapable of movement, power does not disappear; it migrates. We will see the rise of ad-hoc coalitions, regional fortresses, and raw bilateral force—a return to the pre-1914 world, but with nuclear weapons. The UN will remain as a ceremonial hall, a museum of good intentions, while the real decisions are made in backrooms in Delhi, Washington, and Beijing, unmoored from even the pretense of international law. Hannah Arendt warned us of this hollowing out of authority:

Power and violence are opposites; where the one rules absolutely, the other is absent. Violence appears where power is in jeopardy, but left to its own course it ends in power’s disappearance.

– Hannah Arendt

By expanding the veto, we are not sharing power; we are ensuring its disappearance into the void of bureaucratic violence.

Prescription: Abandoning the Altar

The prescription, then, is the most difficult pill to swallow: we must stop trying to save the patient in its current form. We need to let the idea of the 1945 Security Council die so that something living can take its place. This does not mean abandoning global cooperation; it means abandoning the hierarchy that stifles it. The goal for India, and for the Global South, should not be to join the club of the veto-wielders, but to dismantle the club entirely.

We need a ‘preventive medicine’ that reimagines global governance not as a council of warlords, but as a network of interdependence. This means stripping the veto power entirely, from everyone. It means moving toward a system of weighted majorities that reflects population and contribution, not historical military victory. It requires the courage to say that the old gods are dead, and that sitting on their thrones will not make us divine. It will only make us complicit in the stagnation that is slowly killing our collective future.