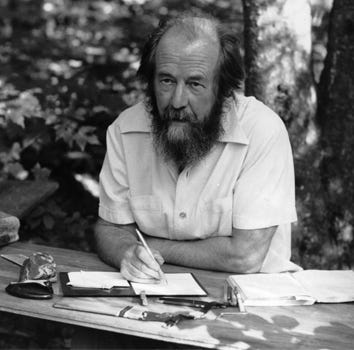

The Bureaucratic Death Trap: Why Solzhenitsyn's Warning About Systems Still Echoes Today?

Have you ever wondered why good people sometimes do nothing in the face of injustice, or why our personal conviction seems to fray when confronted by 'the system'? We dive deep into Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's profound insights to uncover how the seemingly innocuous machinery of bureaucracy subtly dismantles individual courage, transforming us from active moral agents into cogs in a larger, often unethical, apparatus. This isn't just history; it's a chilling contemporary prophecy.

The Big Question: The Quiet Assassination of Conscience

We often imagine courage as a grand, heroic act—standing up to a dictator, resisting overt tyranny, or facing down physical danger. But what about the quieter, more insidious forms of suppression that erode our moral backbone without a single shot being fired or a single decree being shouted? This is the central enigma I want us to explore today: How does the very structure of bureaucracy, designed for order and efficiency, also become a silent assassin of individual courage and ethical conviction? It’s a question that haunted Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in the brutal gulags of the Soviet Union, and one that, I contend, is profoundly relevant to our lives in ostensibly free societies today.

Solzhenitsyn, through his harrowing experiences and profound reflections in "The Gulag Archipelago", exposed not just the overt cruelty of a totalitarian regime, but also the subtle mechanisms by which ordinary individuals, even those with good intentions, could become complicit or simply inert within a vast, impersonal system. He witnessed firsthand how the endless paperwork, the chain of command, the diffusion of responsibility, and the sheer overwhelming scale of the apparatus could gradually chip away at a person's willingness to speak truth to power, to object to injustice, or even to recognize their own moral obligations. We might not live under a gulag, but the psychological principles Solzhenitsyn unveiled about systemic pressure are universal, and understanding them is our first step towards resistance.

The Silent Erosion: Bureaucracy's Invisible Hand

At its core, bureaucracy is a fascinating paradox. On one hand, it represents the rationalization of society, the attempt to manage complex operations through predictable rules, specialized roles, and hierarchical structures. Max Weber famously described it as the most efficient form of organization, a necessary engine for modern states and large corporations. The thesis, then, is that bureaucracy is an indispensable tool for order, fairness, and accountability—at least in theory. It's supposed to prevent arbitrary power by subjecting all to the same rules, ensuring consistency and impartiality.

However, the antithesis emerges when we examine the human cost of this very efficiency. The strict division of labor, the emphasis on following protocol, and the hierarchical command structure often lead to a profound fragmentation of moral responsibility. When a decision goes wrong, or an injustice occurs, it's incredibly difficult to pinpoint who is truly accountable. Everyone is just "following orders" or "doing their job," diffusing culpability across an entire apparatus. Individuals become specialists in narrow tasks, losing sight of the broader ethical implications of their collective work. This psychological distancing, where one is insulated from the direct consequences of their actions, is a critical ingredient in the quiet erosion of courage. The system itself becomes the agent, not the people within it.

The synthesis, therefore, is that while bureaucracy is structurally designed to handle complexity and ensure consistency, its very design inadvertently creates conditions ripe for moral passivity. It's not that bureaucracies actively seek to destroy courage, but rather that the inherent logic of such systems—prioritizing procedure over principle, role over person, and compliance over conscience—pushes individuals towards inaction. This structural insulation from personal accountability is the invisible architecture that often facilitates collective moral failure. It's a subtle but powerful force, turning potential heroes into silent observers without them even realizing the transformation.

The Solzhenitsyn Effect: When Conscience Withers

The insights of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn provide a chilling, real-world testament to this bureaucratic death trap. In "The Gulag Archipelago," he meticulously documented how the Soviet system, an extreme but illuminating example of bureaucratic machinery, could warp human morality. He wrote about the moment an individual chooses silence, often out of a perfectly understandable fear for their own life or the lives of their loved ones. But what Solzhenitsyn illuminates is how these individual, rational choices accumulate to create a collective moral void.

“And how we burned in the camps later, thinking: What would things have been like if every Security operative, when he went out at night to make an arrest, had been uncertain whether he would return alive and had to say goodbye to his family? Or if, during periods of mass arrests, people had not simply sat there in their lairs, paling with terror at every knock of the doorbell, but had understood that they had nothing left to lose and had boldly set up an ambush in the hall with a crowbar or an axe?… The Organs would very quickly have run out of officers and transport and, notwithstanding all of Stalin’s thirst, the cursed machine would have ground to a halt!”

– Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, "The Gulag Archipelago"

This powerful lament reveals the core of the "Solzhenitsyn Effect": the understanding that systemic tyranny thrives not just on overt force, but on the predictable conformity and individual failures of courage within its vast bureaucratic network. It's a stark reminder that the erosion of individual bravery, even when it feels like a personal act of self-preservation, has profound societal consequences. This isn't just about totalitarian states; it applies wherever large organizations demand conformity and deferral of responsibility. Consider the whistleblowers who face immense personal and professional costs, or the everyday decisions within corporations where ethical lapses are ignored to maintain the status quo or protect career progression. The bureaucratic apparatus, by its very nature, incentivizes silence over speaking up, compliance over conscience.

“The greatest crimes in the world are not committed by people who are different, but by people who are the same.”

– Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt’s reflections on the "banality of evil" in her analysis of Adolf Eichmann further underscore this point. Eichmann was not a demon but a bureaucrat, a man who saw his role as managing logistics rather than participating in mass murder. His defense was that he was merely following orders, operating within a system. This highlights how systems can de-humanize, abstracting the consequences of actions and allowing individuals to disassociate from their moral implications. This psychological distancing is precisely what we must guard against, for it is here that courage is most subtly, yet effectively, suppressed.

Reclaiming Agency: Cultivating Moral Fortitude in the Machine

So, what can we do? How do we reclaim our agency and cultivate moral fortitude when confronted by the overwhelming power of the bureaucratic machine? The first step is awareness: recognizing the subtle pressures and the diffusion of responsibility inherent in large systems. I encourage you to pause and reflect on situations where you've felt your ethical compass waver due to systemic forces. Was it a policy you disagreed with but followed? A colleague's questionable behavior you overlooked to avoid conflict?

Cultivating courage within a bureaucratic context requires conscious effort. It means developing a strong personal moral framework that operates independently of the organizational one. This doesn't mean always being a rebel, but it does mean developing the capacity for independent ethical judgment and the willingness to act on it when necessary. This could manifest as:

Questioning the "Why": Don't just follow procedures blindly. Understand the ethical rationale, or lack thereof, behind directives.

Seeking Allies: Find like-minded individuals who share your ethical concerns. Collective courage is often more effective than isolated acts.

Defining Your Red Lines: Know what you will and will not compromise on. Having clear personal boundaries empowers you to resist incremental erosion.

Practicing Small Acts of Courage: Start by speaking up on minor issues. This builds your "courage muscle" for when larger ethical dilemmas arise.

Maintaining External Perspectives: Don't let your entire identity be consumed by your role in the system. Engage with diverse viewpoints outside your organizational bubble.

These aren't easy steps, but they are essential. The goal isn't to dismantle every bureaucracy—many are necessary—but to inoculate ourselves against their potential to diminish our humanity and our capacity for courageous action. It is about actively choosing to remain a conscious moral agent, even when the system conspires to turn you into an unthinking functionary.

A Call to Vigilance: Our Moral Imperative

The "Solzhenitsyn Effect" is a timeless warning. It teaches us that the greatest threats to human freedom and dignity don't always come from overt oppression, but often from the quiet, almost imperceptible pressures of systems that diminish our individual will and moral courage. As citizens, as employees, as human beings, we have a moral imperative to understand these forces and to actively resist them. This means nurturing our capacity for independent thought, maintaining our ethical compass, and finding the courage, however small, to speak and act in alignment with our conscience. Only by doing so can we prevent the bureaucratic death trap from claiming our most precious human attribute: our unyielding courage.

Request: can you chuck in a few footnotes and refs? GULAG ⛓️📚 is three volumes and Arendt ✍🏼 has multiple works. Thanks for the essay either way.

War is by governments