Maurice Blanchot: The Philosophy of Refusal and Political Nihilism

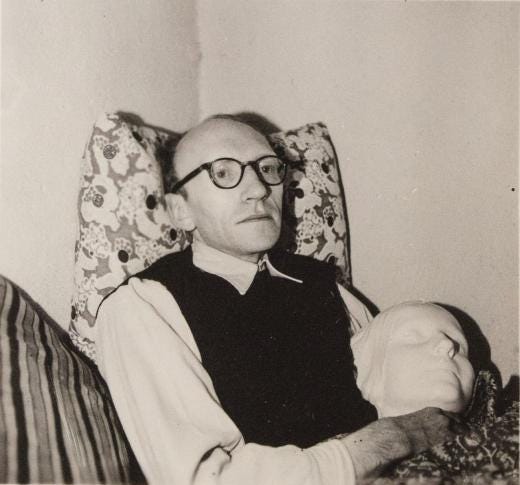

Maurice Blanchot (1907–2003) stands as a towering yet enigmatic figure in French philosophy. His influential body of work has profoundly shaped contemporary thought on literature, politics, and the nature of existence. At the heart of his thinking lies the concept of refusal—a critique of traditional political representation that emphasizes the power of silence and absence in articulating dissent.

Blanchot’s exploration serves as a critical lens through which we can examine today’s culture of negation and political nihilism. He proposes that the act of refusal is not merely a withdrawal, but a significant form of resistance that exists outside conventional frameworks of identity and ideology.

Life and Work: A Journey into Silence

Early Life and Literary Contributions

Born into a wealthy family in 1907, Blanchot pursued his education at the University of Strasbourg and the Sorbonne. It was here that he forged a significant friendship with philosopher Emmanuel Lévinas, who introduced him to the phenomenology of Husserl and Heidegger. While his early years were marked by controversial right-wing journalism during the tumultuous 1930s, the onset of World War II triggered a pivotal shift in his focus toward literary and philosophical exploration.

Blanchot’s work merges fiction with critical theory, addressing profound themes such as mortality, language, and the ethical dimensions of writing. His influential monographs, including The Space of Literature and The Writing of the Disaster, underscore a Hegelian form of negation. He argues that literature possesses a transformative potential to challenge and reshape our understanding of existence.

I don’t say that the author doesn’t exist... I say that the author does not precede the works. He is a certain functional principle by which, in our culture, one limits, excludes, and chooses.

Michel Foucault

This intersection of the author’s disappearance and the emergence of the text is central to Blanchot’s legacy. He was known for his intense privacy, famously stating that his life was “wholly devoted to literature and to the silence unique to it.”

The Philosophy of Refusal

Blanchot’s philosophy offers a profound critique of contemporary political discourse. He emphasizes that refusal is not simply a negation, but an active, silent statement that reveals the gaps in representation within political structures. This refusal arises from a “very poor beginning,” signifying a voice that traditional political discussions fail to represent.

The Aesthetics of Rejection

In the context of modern activism, Blanchot’s reflections align with movements that reject established forms of political representation. He suggests that even movements lacking a coherent identity or unified agenda can embody powerful resistance. Key characteristics of this philosophy include:

Categorical Rejection: A total critique of the techno-political order governing modern society.

Absence of Program: By refusing to articulate a clear program, movements expose the limitations of existing systems.

Political Agency: The act of refusal itself serves as a form of agency, existing outside of programmatic unity.

The only way to deal with an unfree world is to become so absolutely free that your very existence is an act of rebellion.

Albert Camus

Historically, this draws from forms of resistance like wildcat strikes and grassroots movements—actions that bypass traditional institutions. Blanchot and contemporaries like Dionys Mascolo coined terms like “literary communism” to describe this ethos, suggesting that refusal fosters a new understanding of solidarity that transcends established identities.

The Culture of Negation

The culture of negation is intricately tied to Blanchot’s conception of literature and its relationship with truth. He posits that literature operates through a negation that separates things from themselves, destroying them in a quest for knowledge. This results in “meaningful prose,” where literature safeguards the movement of meaning transforming into truth.

Blanchot extends this to political philosophy, drawing parallels between literature and revolutionary action. Both involve a conceptual negation of ordinary reality. In his essay Literature and the Right to Death, he emphasizes language as a negating power, arguing that existence is made significant through the labor of the negative.

Influence on Political Thought and Community

Blanchot’s assertions about the decline of revolutionary fervor highlight a shift in how we perceive politics. He famously stated that we must become conscious of our position at “the end of history,” urging a re-evaluation of inherited revolutionary notions.

The Burden of Responsibility

Moving away from nationalism or fusion, Blanchot posits a transformative understanding of community. He argues for a community that witnesses an infinite demand for justice, transcending self-identity. This involves bearing witness to an “impossible responsibility” towards the nameless other.

The tie with the Other is knotted only as responsibility, whether accepted or refused, whether knowing or not knowing how to assume it, whether able or unable to do something concrete for the Other.

Emmanuel Levinas

This perspective is vital for analyzing modern protests, which often reject traditional affiliations in favor of anonymous engagement. In a world defined by fractured identities and market-driven social movements, Blanchot rejects the nostalgia for community. Instead, he frames community as a complex task requiring practical judgment and the resolution of conflict.

Legacy and Reception

Maurice Blanchot passed away in 2003, but his legacy persists. His exploration of intimacy, separation, and the “infans” (the unexpressed elements within individuals) continues to influence poststructuralism and deconstruction. Figures like Jacques Derrida have acknowledged their immense debt to his work regarding the autonomy of language and the non-instrumentality of literature.

By framing financial capitalism in terms of extinction and ecological crisis, Blanchot’s later ideas also encourage a critical re-evaluation of economic practices. Ultimately, his work invites us to engage with literature and politics not as static fields, but as sites of philosophical inquiry that interrogate the very nature of being, identity, and the human condition.