How Walter Benjamin’s Prophecy Unmasks AI’s Spiritual Impoverishment

Walter Benjamin’s concept of ‘aura’ offers a profound lens through which to examine the unsettling spiritual emptiness of AI-generated culture. When art and creative expression can be infinitely replicated and algorithmically manufactured, what becomes of their unique presence, their authenticity, and their connection to ritual and history? This deep guide explores how AI, far from democratizing art, may be completing its desacralization, leaving us awash in a sea of technically perfect, yet soulless, creations.

The Unsettling Perfection of the Algorithmic

There is a growing unease in the cultural landscape, an unspoken apprehension that whispers beneath the surface of our dazzling technological advancements. We marvel at AI’s ability to generate breathtaking images, compose intricate music, and craft compelling narratives, often indistinguishable from human creations. Yet, beneath this veneer of perfection, many of us sense a spiritual hollowness, a missing spark that defies algorithmic replication. It’s as if AI art, for all its technical brilliance, arrives without a soul, presenting us with flawless forms devoid of the unique presence that has historically defined art’s power.

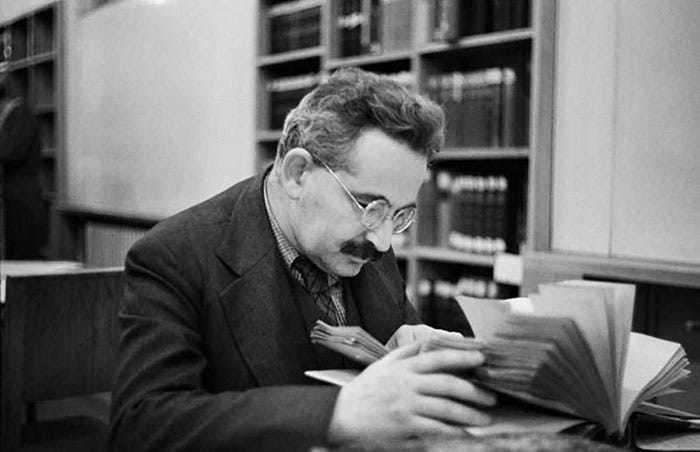

This feeling is not merely aesthetic snobbery; it touches upon something fundamental about how we connect with cultural artifacts and, by extension, with our shared humanity. To truly understand this burgeoning crisis of authenticity, we must turn to a prescient thinker from a century ago: Walter Benjamin. In his seminal essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Benjamin introduced the concept of the ‘aura’ – a unique quality he argued was inherent in a work of art due to its singular existence in time and space, its history, and its connection to ritual. He foresaw how technologies like photography and film would begin to erode this aura, but could not have imagined the totalizing force of AI. Today, AI’s infinite replication capabilities are not merely reproducing art; they are fundamentally altering our relationship with creation, stripping away the very essence that once made art sacred and meaningful.

The Genesis of Aura: Benjamin’s Vision of Unique Presence

To grasp the full impact of AI on art, we must first immerse ourselves in Walter Benjamin’s profound concept of ‘aura.’ In the 1930s, as Europe teetered on the brink of war and new technologies like photography and cinema began to transform cultural consumption, Benjamin articulated a crucial insight. He defined aura as “the unique phenomenon of a distance, however close it may be.” This wasn’t just about physical distance, but an almost mystical quality derived from a work’s singular existence in time and space. A painting by Rembrandt, for instance, possesses an aura because it is the original; its physical presence bears the traces of its history, its creation, its owners, and the rituals it has been part of – whether in a cathedral or a museum. This unique presence lends the original a certain authority and authenticity that cannot be replicated.

Benjamin argued that aura was deeply intertwined with ritual and tradition. Early artworks, he observed, often served religious or cultic functions. Their value was not primarily aesthetic but ritualistic, and it was this embeddedness in tradition that gave them their profound, almost sacred, presence. Even as art moved from ritual to exhibition, some echoes of this sacredness persisted, granting the original work a reverence. The slow decay of a fresco, the subtle cracks in an oil painting – these imperfections became part of its story, enhancing its unique aura. What Benjamin lamented was that mechanical reproduction threatened this very uniqueness, detaching the artwork from its historical context and its ritualistic roots. He saw this as both a loss and a potential gain, opening art to new, more democratic political functions, but unequivocally dissolving its traditional authority.

Mechanical Reproduction’s First Strike: Photography and Film

Benjamin meticulously detailed how photography and cinema, the dominant mechanical reproduction technologies of his era, began to chip away at art’s aura. A photograph of a masterpiece, for example, could be endlessly replicated and distributed, bringing the image of the art to the masses but fundamentally severing it from the original’s unique presence. The photograph itself might acquire its own aura, but the aura of the original painting was diminished in its mediated form. The cinema took this a step further, presenting a dynamic, mass-produced experience where the very concept of an ‘original’ film strip was less significant than the collective experience of its projection. The actor, Benjamin noted, performed for a camera, not a live audience, and their aura was fragmented, constructed through editing and multiple takes. The performance itself became a commodity, detached from the unique, ephemeral presence of the stage actor.

Even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be.

– Walter Benjamin

This early phase of mechanical reproduction introduced the public to art in a new, accessible way. It democratized aesthetics, bringing images and stories to millions who might never visit a museum or attend a live play. However, this democratization came at a cost. The proliferation of copies meant that the special, singular quality of the original was diluted. The value shifted from the unique presence to the political or social message that could be conveyed through mass distribution. While Benjamin saw revolutionary potential in this shift, particularly for political engagement, he was acutely aware of the spiritual trade-off: the art object’s intrinsic, almost sacred, authority was being systematically undermined.

AI’s Infinite Replication: The Ultimate Hyper-Reality

If mechanical reproduction began the erosion of aura, then artificial intelligence represents its conclusive obliteration. AI doesn’t merely replicate existing art; it generates entirely new ‘artworks’ with unprecedented speed and volume. These creations, whether images, texts, or melodies, are born without a history, without a unique origin in the human struggle of creation, and without a singular presence in time and space. They are literally infinite variations, generated on demand, each a perfect simulacrum, yet none possessing the ‘here and now’ that Benjamin deemed essential to aura. This marks a significant departure from even photography; a photograph still captures a moment, a specific reality, however detached. AI, by contrast, conjures from pure data, creating a hyper-reality that never existed. What are we to make of an artwork that can be summoned into existence, altered, and discarded with a simple prompt, indistinguishable from a million others?

This is where AI takes us beyond mere reproduction into what Jean Baudrillard might call the realm of the ‘simulacrum’ – a copy without an original. An AI-generated piece of art has no ‘original’ in the traditional sense; it is a statistical average, a digital hallucination. It lacks the artist’s struggle, their intention, their unique life experience poured into the medium. The spiritual emptiness emerges from this lack of human imprint, this absence of a unique journey that culminates in a singular expression. When anything can be art, and everything can be generated on command, the very concept of art as a special, significant human endeavor begins to dissolve. We are not just losing aura; we are losing the very ground upon which authentic meaning is built.

The Spiritual Emptiness of the Algorithmic

The core of the problem with AI-generated art, from a Benjaminian perspective, is its inherent spiritual emptiness. Aura, for Benjamin, was tied to the object’s unique history and its embeddedness in ritual. AI-generated art has no such history; it is born instantaneously from a cold algorithm, devoid of the passage of time, the touch of a human hand, or the context of a particular moment of creation. It exists purely as a functional output, a technical achievement, not as an expression imbued with personal or collective meaning. This is why, despite their visual perfection, these creations often leave us feeling strangely unmoved. They are aesthetically pleasing, perhaps even beautiful, but they lack the resonant depth that compels us to pause, to reflect, to feel a connection to something larger than ourselves.

The ultimate consequence of this process is that the work of art ceases to be an object of contemplation and becomes a stimulus for experience.

– Max Weber, though reflecting Benjamin’s broader concerns about disenchantment.

Consider the difference between beholding a masterpiece forged through centuries of artistic tradition and scrolling through a feed of AI-generated landscapes. One invites contemplation, a sense of wonder, a connection to a specific human story and cultural lineage. The other offers novelty, entertainment, and efficient visual stimulation, but rarely demands deeper engagement. This shift from contemplation to mere experience, from reverence to consumption, is the very essence of spiritual impoverishment. The profound challenge of our algorithmic age is that we are trading genuine, unique presence for boundless, frictionless availability, and the cost is the soul of our cultural output. It’s a trade-off that leaves us surrounded by technically stunning artifacts, yet starved for true meaning.

The Devaluation of the Creator: Humanity’s Place in the Art World

Beyond the art object itself, AI’s impact reverberates through the very role of the human creator. If algorithms can generate infinite variations of a style, produce technically perfect compositions, or mimic the brushstrokes of a master, what becomes of the human artist? The romantic notion of the artist as a singular genius, channeling divine inspiration or unique vision, is severely challenged. While some might argue that AI is merely a tool, an extension of the artist’s hand, the sheer autonomy and generative capacity of these systems raise profound questions about authorship, originality, and the value of human labor in creative fields. If a machine can ‘paint’ a portrait in the style of Rembrandt in seconds, does it diminish the value of a human artist who spends years perfecting their craft?

This devaluation isn’t just economic; it’s existential. Creativity, for humans, is often a journey of self-discovery, a means of processing the world, expressing inner truths, and connecting with others. The struggle, the failure, the breakthrough – these are all integral to the human creative process. When AI bypasses this struggle, offering instant gratification and flawless output, it threatens to render the human creative endeavor redundant, or at least less significant. We risk losing the profound meaning we derive from creating, from seeing our unique perspectives materialized in the world. As I observe this trend, I can’t help but feel that we are not just outsourcing tasks, but offloading a fundamental part of our human experience onto machines, with little understanding of the spiritual void this might create within us.

The Spectacle of Originality: Mimicking Creation Without Genuine Origin

AI doesn’t just produce copies; it produces a convincing spectacle of originality. It can invent entirely new styles, cross-pollinate genres in novel ways, and generate outputs that appear startlingly fresh. Yet, this ‘originality’ is a clever mimicry, a statistical recombination of existing data, rather than a genuine emergence from a lived experience or a unique perspective. It creates the illusion of a new origin, a distinct beginning, when in reality it is an advanced form of pattern recognition and synthesis. This makes the erosion of aura even more insidious: we are not just seeing copies of originals, but ‘originals’ that have no authentic point of origin in human experience.

This phenomenon, where the simulated becomes more compelling or more prevalent than the real, has profound implications for our understanding of truth, authenticity, and value. If an AI can generate a more ‘original’ idea faster and more efficiently than a human, does the human idea still hold its weight? This leads to a kind of Baudrillardian hyperreality in art, where the map precedes the territory, and the generated image or text becomes the new benchmark for what is considered ‘creative,’ even if it is fundamentally an echo chamber of past human effort. We must ask ourselves if we are truly advancing human creativity or simply drowning in an endless, flawless stream of simulations.

Reclaiming the Sacred in a Simulated World: Cultivating Conscious Engagement

The question then becomes: how do we, as conscious beings, navigate this new landscape without succumbing to the spiritual emptiness of the algorithmic void? The answer, I believe, lies in a deliberate act of resistance and reclamation. We must consciously cultivate a deeper, more intentional relationship with art and creativity. This means prioritizing human-made art, not out of Luddite rejection of technology, but out of a recognition of its irreplaceable human value. It means seeking out the unique, the handmade, the imperfect, the art that carries the unmistakable trace of a human struggle and a human story. It means understanding that the ‘value’ of art is not solely in its aesthetic perfection, but in its capacity to connect us to profound truths, to shared experiences, and to the unique vision of another human being.

Practically, this could mean supporting human artists directly, seeking out galleries and independent creators, or simply pausing to truly see a piece of art, rather than merely consuming it. It means distinguishing between the convenience of AI-generated content and the irreplaceable depth of human-authored work. We must become discerning curators of our own cultural consumption, choosing to engage with works that challenge, inspire, and connect us on a deeper level. This isn’t about shunning AI, but about re-centering human experience as the ultimate arbiter of cultural value. Our task is to ensure that while AI may make everything ‘art,’ it does not make nothing sacred.

The Third Citizen’s Path: Synthesizing a Way Forward

Drawing from Benjamin’s insights, our path forward is not one of outright rejection, but of critical synthesis. We acknowledge AI’s undeniable utility and its potential for innovation, but we refuse to let it define the entirety of our cultural experience. The thesis is AI’s boundless capacity for generating technically perfect art; the antithesis is the spiritual void this perfection creates, dissolving the aura and meaning of art. The synthesis lies in consciously reclaiming the value of human authorship, intentionality, and the unique, irreplaceable presence that only human creation can offer. This means fostering spaces – both physical and digital – where the human touch is celebrated, where the story behind the art is as important as the art itself, and where the act of creation is valued for its inherent humanity, not just its output.

We must champion the idea that art is not merely a product, but a process; not just an image, but an experience; not just a dataset, but a soul made manifest. This re-prioritization of the human element will safeguard the sacred in a world increasingly saturated with the simulated. It demands that we ask not just ‘what can AI create?’ but ‘what do we, as humans, truly value in creation?’ By answering that question with conviction, we can ensure that the spiritual core of art endures, even as the machines learn to mimic its form.

Final Reflections: Rekindling the Flame of Genuine Meaning

Walter Benjamin’s observations about the death of aura are more relevant now than ever, offering a profound warning about the spiritual costs of technological advancement. As AI proliferates, making everything art and simultaneously stripping art of its unique sacredness, we face a crucial juncture. The challenge is not to fear technology, but to understand its true implications for human meaning and value. We must learn to distinguish between technical prowess and profound significance, between endless replication and unique presence. Our task, as custodians of culture and meaning, is to resist the gravitational pull towards frictionless consumption and to actively seek out, support, and cherish the art that carries the authentic spark of human intention. Only then can we ensure that the flames of genuine meaning continue to burn brightly, illuminating our shared human journey.

The part about the 'aura' and its definable existence within time and space reminded me a lot about the works of John Berger (art critic, author, painter). He talked about the way we view art and how it's changed through the advancements of technology as well. I found his book 'Ways of Seeing' to be very enlightening on this topic. Its interesting to wonder how all these philosophers would deal with the problems we are now encountering with AI. It is getting to be scary out there for artists.