How Absolute Freedom Shapes (and Shakes) Progress

Mill's Unsettling Truth

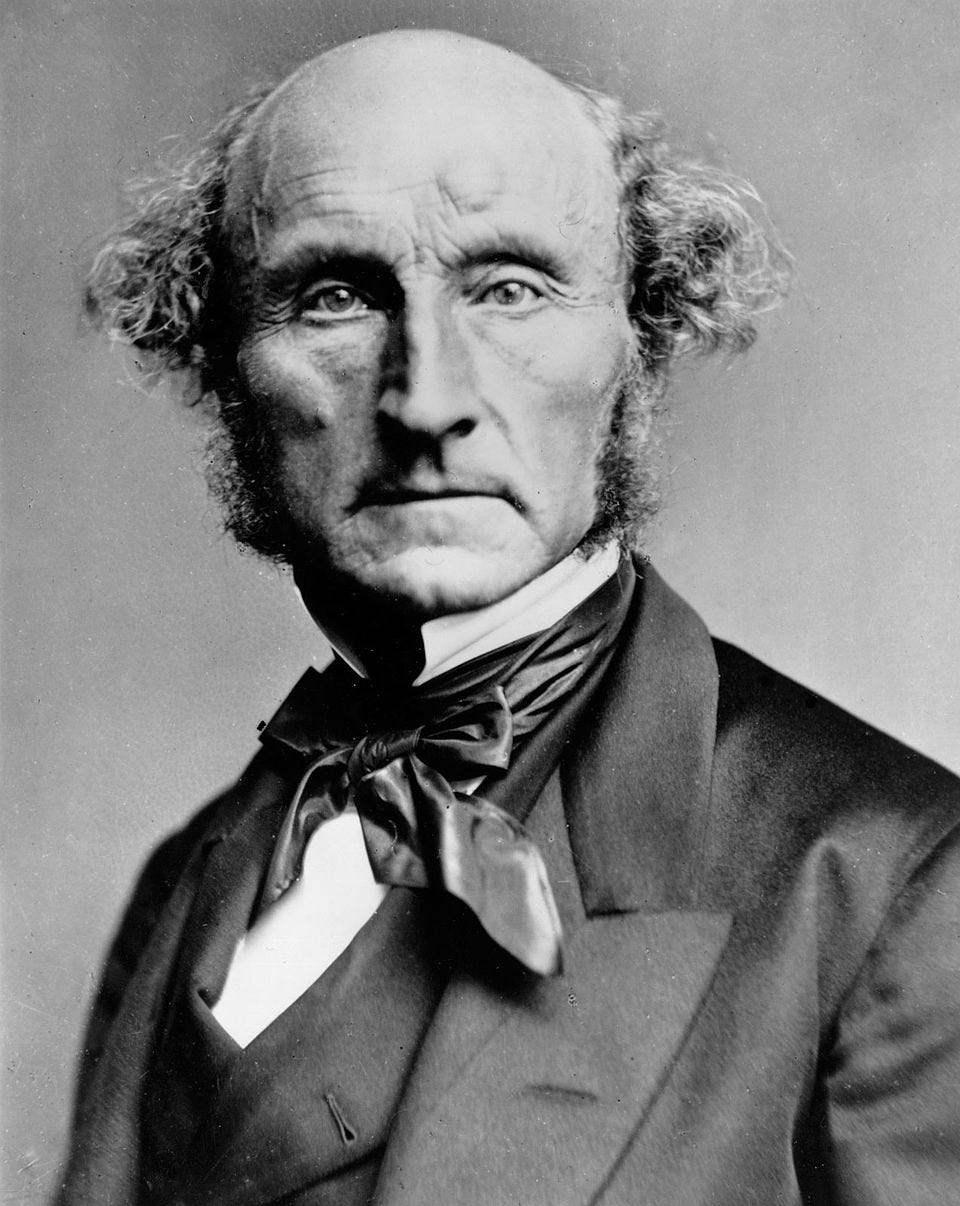

John Stuart Mill's "On Liberty" remains a cornerstone of liberal thought, arguing that individual freedom is not just a right but the engine of social progress. Yet, his ideas present a complex truth: unchecked liberty can create unforeseen challenges, forcing us to confront the delicate balance between individual autonomy and collective well-being. This guide explores Mill's profound insights, their enduring relevance, and the unsettling questions they pose for our modern world.

The Unseen Chains of Conformity: Why Mill Still Speaks to Us

In an age increasingly defined by echo chambers, digital tribalism, and the subtle pressures of conformity, the words of John Stuart Mill resonate with an unsettling prescience. His seminal work, "On Liberty," published in 1859, laid a philosophical cornerstone for the notion that individual freedom is not merely a right, but the very engine of social progress. Mill argued that only through unfettered expression, radical individuality, and the open clash of ideas could humanity truly advance, evolving beyond outdated customs and injustices.

For me, Mill's enduring power lies not just in his advocacy for liberty, but in his profound understanding of its inherent complexities. He saw that while freedom could liberate, it could also expose society to new vulnerabilities. The simplicity of his ideal—that individuals should be free to pursue their own good in their own way—belies a profound, ongoing challenge: what happens when the pursuit of absolute freedom clashes with the need for collective well-being? Where do we draw the line when one person's liberty appears to infringe upon another's? These are not abstract academic questions, but dilemmas that confront us daily, from the digital public square to the very fabric of our communities. To truly grasp Mill's legacy is to grapple with this intricate dance between the individual spirit and the societal whole, a dance that continues to shape our present and define our future.

Echoes of Empire: Mill's World and Ours

To understand Mill's radical ideas, we must first immerse ourselves in his world. John Stuart Mill's philosophical work emerged during Britain's transformative Victorian age (1837–1901), a period of sweeping reforms across education, politics, and economics. This era was fundamentally shaped by the Enlightenment's ideals of justice and reason, ignited by the American and French revolutions, which spurred fervent calls for improvement, human happiness, and, of course, liberty.

Mill’s intellectual development was profoundly influenced by the debates of his time, particularly regarding the nature of happiness and the role of government. He was exposed to various philosophical traditions, including Benthamite utilitarianism, which focused on applying laws to achieve societal benefits. However, Mill’s philosophy also grappled with a significant shift from raw individualism towards collectivism, a trend he observed emerging in late nineteenth-century discourse. Despite this, he remained a steadfast believer in self-help and local enterprise as crucial for societal progress, reflecting the dominant Victorian ethos.

The only freedom which deserves the name, is that of pursuing our own good in our own way, so long as we do not attempt to deprive others of theirs, or impede their efforts to obtain it.

– John Stuart Mill,

The Bedrock of Progress: Mill's Core Vision of Liberty

At the heart of Mill's philosophy lies an unwavering conviction: liberty is not merely a desirable state, but an absolute prerequisite for both individual flourishing and societal progress. He posits that freedom of thought and action creates the fertile ground upon which individuals can truly develop their unique talents and contribute to the greater good. This isn't just about tolerance; for Mill, unchecked liberty is fundamental to achieving rational consensus and a just society.

Mill fiercely critiques any method of achieving social agreement through coercion, exemplified by his disagreement with thinkers like Auguste Comte, arguing that such approaches ultimately compromise individual freedom. This, to Mill, is unacceptable, as personal liberty is the indispensable foundation for human development. This concept of "individual sovereignty" is central to his ethics, asserting that each person holds the absolute right to govern their own body and mind. True freedom, in his view, means pursuing one's own good in one's own way, provided it does not infringe upon the rights of others. This assertion was a direct challenge to the prevailing social norms of his time, advocating for a more individualized understanding of liberty that champions self-determination and personal responsibility.

The Harm Principle: Freedom's Boundaries and Its Ethical Tightrope

Perhaps Mill's most famous and oft-debated concept is the harm principle. It asserts that "the only legitimate reason for interfering with an individual's liberty is self-protection." In essence, you are free to act as you choose, as long as your actions do not harm others. This principle serves as a crucial safeguard against the potential "tyranny of the majority" in a democratic society, ensuring that a national character supporting progressive interests can truly emerge.

Yet, the apparent simplicity of the harm principle quickly unravels when we try to apply it to the messy realities of human interaction. Mill meticulously distinguishes between "harm" and mere "offense," arguing that only actions causing significant injury to others warrant restrictions on liberty. Not all unwelcome consequences or expressions of distaste qualify as harm. This nuanced view attempts to establish a clear boundary for societal intervention, but the delineation itself is the subject of endless debate. What constitutes 'significant injury'? How do we measure harm that isn't physical, such as psychological distress or economic disadvantage? The fundamental tension lies in discerning where one's liberty ends and another's begins, especially when "harm" can be both tangible and unseen. This ethical tightrope walk is precisely what makes the harm principle both revolutionary and perpetually challenging.

Free Speech: The Crucible of Truth and the Peril of Silence

Mill was a passionate advocate for free speech, seeing it as absolutely vital for intellectual and social advancement. He believed that silencing opinions, even those we deem false or offensive, robs society of the opportunity to discover truth. For Mill, the free exchange of ideas is a dynamic process through which individuals reassess their beliefs, allowing society to avoid the stagnation of dogmatism. He famously argued that even a false opinion, when openly discussed, serves a crucial purpose: it forces us to re-examine and strengthen our own, potentially true, beliefs.

The danger, as Mill saw it, was not necessarily the propagation of error, but the suppression of debate. He warned that the prevailing opinion might deter dissenting voices, emphasizing the necessity of protecting even false opinions for the sake of truth and progress. In today's digital age, where algorithms curate our information and echo chambers proliferate, Mill's defense of free speech becomes even more urgent. It challenges us to consider whether our desire for comfortable consensus is inadvertently stifling the very intellectual dynamism necessary for genuine societal advancement.

The Cultivation of Self: Individuality as a Moral Imperative

For Mill, the concept of individuality is inextricably linked to the pursuit of "higher pleasures" and, ultimately, overall societal well-being. He believed that the full expression of individual character is a crucial element in achieving the summum bonum of utilitarianism – the greatest happiness for the greatest number. In his view, a society where individuals are encouraged to develop their unique selves, express their diverse talents, and live according to their convictions is inherently a more vibrant, innovative, and ultimately happier society.

This connection between liberty and personal fulfillment underscores Mill's conviction that social progress is inherently tied to the protection of individual rights and freedoms. When individuals are stifled, when conformity is enforced, the wellsprings of creativity, innovation, and moral development dry up. Therefore, the cultivation of self, far from being a selfish pursuit, becomes a moral imperative that contributes directly to the collective good. It is through diverse experiments in living that new and better ways of life are discovered, enriching all.

Utility's Guiding Hand: Secondary Principles in a Complex World

While Mill is often associated with pure utilitarianism – the idea that actions are right if they promote happiness and wrong if they produce unhappiness – he understood that life's moral landscape is far too complex for constant, on-the-spot calculations of utility. This led him to introduce the concept of "secondary principles." These are not rigid rules, but rather reliable, albeit imperfect, guides for ethical decision-making. He likened them to navigational tools that aid us in traversing a complex moral sea without having to exhaustively calculate every current and wind pattern.

By adhering to these secondary principles – such as honesty, justice, or fidelity – individuals can navigate moral dilemmas while generally promoting overall happiness, even if the outcomes are not always optimal. This approach acknowledges that while "rules of thumb" may not guarantee perfect results, they are invaluable for guiding actions in a complex moral landscape. This pragmatic application of utilitarianism reveals Mill's deep understanding that ethical philosophy must engage with the practicalities of human experience, providing frameworks that are both idealistic and actionable.

The Unfolding Canvas of Progress: Liberty's Dynamic Dance

Mill contended that social progress is not a static destination but an ongoing, dynamic process. It unfolds primarily when individuals are liberated from restrictive norms and allowed to express their individuality. He saw the struggle for freedom as a continuous, adaptive process, constantly adjusting to the changing dynamics of society. "On Liberty" is, in many ways, a rallying cry for those seeking to defend personal freedoms against both government overreach and the insidious pressures of societal conformity.