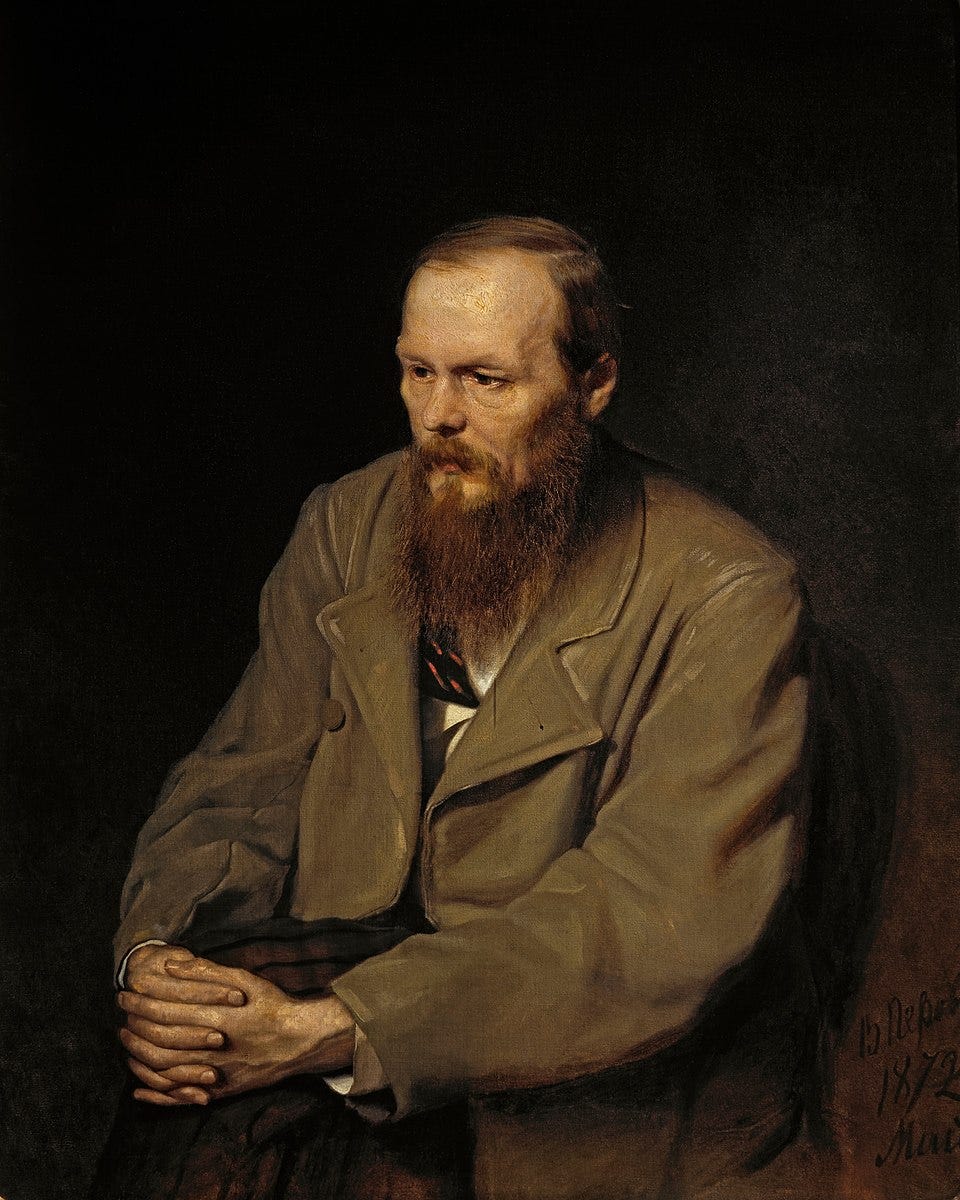

Dostoevsky's Forgotten Warning: Why Endless Comfort Hides Life's Most Profound Truths?

Fyodor Dostoevsky, a literary giant, presented a radical critique of comfort, asserting that the pursuit of ease can lead to moral decay and spiritual emptiness. This deep dive into his philosophy explores how suffering can be a catalyst for growth, empathy, and genuine human connection, challenging our modern societal inclination towards constant comfort and offering a balanced approach to navigating life's inherent adversities.

The Allure of Ease and Its Unseen Costs

I often find myself observing the world around me, particularly the relentless march towards an ever-more comfortable existence. From smart homes anticipating our needs to algorithms curating our experiences, the modern promise is one of effortless living. Yet, I can't help but feel a growing sense of unease. It's in these moments that I turn to thinkers like Fyodor Dostoevsky, whose profound insights, forged in the crucible of 19th-century Russia, offer a powerful counter-narrative to our contemporary obsession with comfort.

Dostoevsky, a novelist whose characters wrestled with the deepest moral and existential questions, didn't merely critique comfort; he presented a philosophical and moral indictment of its overemphasis. He argued that an unchecked pursuit of ease leads to moral decay, a spiritual superficiality, and a dangerous disconnection from the most fundamental truths of our existence. His perspective, deeply informed by his own profound suffering and imprisonment, suggests that adversity is not an obstacle to be avoided, but a vital catalyst for resilience and moral character. This isn't a call for asceticism, but a profound invitation to re-examine the values we unconsciously uphold in our quest for a frictionless life.

Dostoevsky's Vision: Comfort as a False Idol

To Dostoevsky, comfort was far from an unalloyed good. He viewed it with a profound skepticism, suggesting that the pursuit of ease and convenience is often a recipe for weakness and mediocrity. For him, the human spirit is forged in the fires of adversity. Those who confront challenges, whether by choice or by fate, are far more likely to develop the resilience and inner strength necessary for a meaningful life. This idea, which may seem counter-intuitive in our comfort-driven society, is a cornerstone of his philosophy.

Consider his assertion that suffering serves a vital purpose: it refines our senses, stripping away the trivialities that comfort often obscures. This sharpening of perception allows us to appreciate the fundamental aspects of existence, to see the world with greater clarity and depth. He even hints at a paradox: that the engagement with pain can sometimes lead to a deeper, more authentic sense of comfort. This isn't about masochism, but about the profound understanding and peace that can emerge from confronting, rather than evading, life's inherent difficulties. It's a challenging idea, isn't it? To think that the very things we seek to avoid might be the keys to our deepest fulfillment.

The Moral Architecture: Suffering and Responsibility

Central to Dostoevsky's thought is the intricate relationship between suffering, empathy, and moral responsibility. He believed that genuine human connection, and indeed our capacity for moral action, often emerges from shared hardship. Comfort, he warned, can dull our senses, inhibiting meaningful engagement with life's moral complexities. This raises critical questions about how a culture focused on ease might unwittingly perpetuate mediocrity and ethical disengagement. When we become insulated from discomfort, do we also become insulated from the suffering of others, and thus, from our own moral obligations?

“The man who has a conscience suffers whilst acknowledging his sin. That is his punishment.”

– Fyodor Dostoevsky

Dostoevsky’s narratives are replete with characters who achieve moral awakening and redemption precisely through their struggles. Think of Raskolnikov in

The Illusion of Peace: When Ease Becomes Paralysis

Dostoevsky issued a stark warning against the dangers of seeking comfort through what he termed 'warped and sinful ways.' He argued that such pursuits, devoid of genuine ethical grounding, ultimately lead to a hollow existence, lacking true peace and happiness. For him, authentic moral action springs from a heightened sensitivity to ethical dilemmas, a sensitivity that is tragically blunted by a life centered on unexamined comfort. When we constantly strive to smooth over every rough edge of existence, we risk losing the very capacity to feel, to discern, and to respond to the world's demands.

He believed that embracing suffering, rather than running from it, facilitates a deeper connection to oneself and to others. It allows us to cultivate empathy and compassion amidst life's inevitable trials. This is not a romanticization of pain, but a recognition of its transformative power. In our relentless pursuit of comfort, we risk amputating the very parts of ourselves that are capable of profound moral growth and genuine human connection.

Societal Erosion: The Collective Unconsciousness of Comfort

The implications of Dostoevsky’s critique extend beyond the individual, reaching into the very fabric of society. He observed that a collective overemphasis on comfort can have significant repercussions for both individual moral development and the well-being of the community. Comfort, he posited, often leads to a pervasive weakness and mediocrity, particularly when people resist the discomfort associated with growth and transformation.

In many societies, there is a tendency to find solace in a 'collective unconsciousness,' a shared reluctance to acknowledge that life can be arranged differently or that challenging the status quo is necessary. This resistance to change, rooted in a fear of confronting discomfort, stifles progress. When individuals and societies cling to familiar comforts, even out of a sense of pity for their own perceived limitations, they perpetuate a cycle of mediocrity, limiting moral engagement and social responsibility. It's a profound thought: are we, as a society, choosing comfortable stagnation over challenging growth?

The Indispensable Role of Adversity

Dostoevsky’s perspective powerfully emphasizes the importance of adversity in shaping moral character. He contended that facing challenges does not merely refine our understanding of moral values but actively fosters empathy and compassion for others. When we personally navigate hardship, we develop a deeper, more visceral understanding of what others endure, making us more attuned to their suffering and more inclined to act with genuine care.

In contrast, a culture overly focused on comfort risks hindering the development of these essential qualities, leading to a diminished sense of community and ethical responsibility. When personal comfort takes precedence over collective well-being, the social fabric inevitably strains, weakening the bonds that hold society together. The idea is that true community isn't built on shared ease, but often on shared struggles and the mutual support found within them.

The Counter-Narrative: Comfort as a Prerequisite for Flourishing

Of course, Dostoevsky's stark critique of comfort doesn't go unchallenged. Many proponents of well-being argue that a foundational level of ease and security is not a detriment, but a prerequisite for individuals to cultivate moral virtues and engage meaningfully with the world. They contend that comfort, in its basic form, provides a stable platform from which people can develop empathy, compassion, and ethical considerations, rather than leading to weakness.

Consider Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, a widely accepted psychological framework. It posits that basic physiological and safety needs must be met before individuals can pursue higher-level needs like belonging, esteem, and self-actualization. A safe and comfortable environment, in this view, is essential for individuals to realize their full potential and participate actively in moral community life. How can one contemplate altruistic pursuits or complex moral reasoning if they are constantly preoccupied with survival?

“What is hell? I maintain that it is the suffering of being unable to love.”

– Fyodor Dostoevsky

Furthermore, the field of positive psychology highlights the crucial role of happiness and well-being in a fulfilling life. Critics of Dostoevsky’s position might argue that an exclusive emphasis on suffering risks overlooking the immense value of positive experiences. They contend that interventions aimed at increasing happiness can improve overall mental health and well-being, making individuals more capable of moral action. From this perspective, focusing on positivity and comfort doesn't negate moral considerations; rather, it enhances one's capacity to care for others and contribute positively to society.

Towards a Balanced Approach: Reconciling Opposing Views

This is where the dialectic truly comes alive. We have Dostoevsky's thesis: comfort can hollow out moral life. We have the antithesis: basic comfort is essential for flourishing. How do we synthesize these seemingly opposing viewpoints? We must recognize that moral life is multifaceted, demanding both an acknowledgment of suffering and a wise embrace of comfort. The relationship between suffering and comfort is not a simple dichotomy but a nuanced paradox.

While suffering can undeniably foster resilience and insight, seeking a certain degree of comfort and ease can also create crucial opportunities for moral growth. This perspective suggests that individuals can learn profoundly from both states, and that these experiences are not mutually exclusive. Instead of viewing comfort solely as a potential source of moral decay, we can understand it as a context in which individuals, when properly grounded, can engage with suffering more constructively, leading to a broader and richer understanding of the human experience. The key, perhaps, lies in the intentionality with which we approach both comfort and discomfort.

Living Dostoevsky's Wisdom Today

So, how do we apply Dostoevsky’s challenging insights in our comfort-obsessed world? It’s not about renouncing all comfort, but about cultivating a conscious relationship with it. We can start by:

Embracing Deliberate Discomfort: Seek out challenges, both physical and intellectual, that push your boundaries. This could be learning a new skill, engaging in difficult conversations, or even simple acts like taking a cold shower. These acts build resilience and prevent the senses from becoming dull.

Cultivating Empathy Through Engagement: Instead of insulating ourselves from the suffering of others, actively seek to understand it. Engage with different perspectives, volunteer, or simply listen deeply to those experiencing hardship. This fosters genuine connection and moral responsibility.

Questioning the Illusion of Ease: Be skeptical of promises of frictionless living. Recognize that true fulfillment often lies on the other side of effort, struggle, and genuine engagement with reality, however uncomfortable it may be.

Finding Purpose Beyond Pleasure: Dostoevsky’s characters often found redemption not in pleasure, but in their striving for meaning and moral clarity. Ask yourself what truly matters beyond immediate gratification.

By consciously integrating these principles, we can move beyond a simplistic view of comfort and suffering, forging a moral life that is robust, empathetic, and deeply meaningful.

Reclaiming Depth in a Comfortable World

Dostoevsky’s case against comfort is a powerful invitation to re-examine the very foundations of our contemporary values. His work reminds us that while ease can be appealing, it carries a hidden cost: the erosion of our moral depth, our capacity for empathy, and our connection to life’s profound truths. By understanding his dialectical argument—that life demands both the acknowledgment of suffering and a balanced approach to comfort—we can cultivate a richer, more resilient existence.

Ultimately, the challenge he presents is timeless: will we choose the comfortable path of least resistance, risking spiritual emptiness, or will we embrace the complexities of the human condition, allowing adversity to forge us into more compassionate and morally responsible beings? The choice, as Dostoevsky would remind us, is always ours.

Thank you. This is very thoughtful-provoking!!! I am reminded of JFK’s challenge to go to the moon—not because it is easy, but because it is hard!!

What a nourishing exploration of a difficult truth. Your reflections reminded me of a line from the Bhagavad-gita As It Is: “Happiness and distress come and go like summer and winter; endure them without being disturbed.” It isn’t a call to seek suffering, but to stay awake to the deeper self that can hold both comfort and hardship without losing its heart.

I love how you frame Dostoevsky’s challenge as a conscious relationship with comfort rather than a rejection of it. It echoes the bhakti sense that our real strength isn’t in perfect circumstances, but in the inner connection that suffering can sometimes bring to the surface—a quiet resilience, a tenderness toward others.

Thank you for offering a path that feels both grounded and compassionate.