Arendt's Haunting Prophecy: Why Passive Conformity Is Becoming Our Digital Tyranny?

Hannah Arendt's profound analysis of totalitarianism offers a chilling mirror to our modern world. She warned that genuine political freedom is extinguished not just by overt dictators, but by the slow, insidious creep of ordinary conformity. In this deep guide, we'll explore Arendt's distinctions between authoritarianism and totalitarianism, examine the mechanisms by which societies become complicit in their own subjugation, and confront the unsettling truth that our digital age might be creating the perfect conditions for a 'new totalitarianism' born not of terror, but of apathy and surveillance. Prepare to challenge your assumptions about freedom, responsibility, and the silent forces shaping our collective future.

Arendt's Unsettling Vision: The Banality of Unfreedom

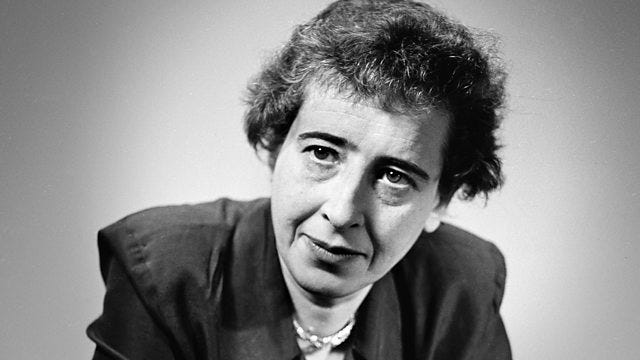

In recent years, many of us have felt a subtle, yet persistent, shift in the socio-political landscape. Crises, amplified by an increasingly interconnected digital existence, have intensified state control and fostered individual isolation. It's in these moments of uncertainty and collective vulnerability that a peculiar kind of danger emerges—a danger Hannah Arendt, one of the 20th century's most incisive political thinkers, spent her life warning us about. She contended that while we often focus on the overt brutality of totalitarian regimes, the true menace lies in the quiet, unthinking compliance of ordinary people. This 'ordinary conformity,' Arendt argued, isn't just a byproduct of tyranny; it's its very precondition.

My aim here is to guide you through Arendt's profound insights, not merely as a historical retrospective, but as a lens through which to understand our contemporary world. We will embark on a dialectical journey, first establishing Arendt's rigorous definition of totalitarianism, then examining the insidious mechanisms through which it operates, and finally synthesizing these historical lessons with our present digital reality. My hope is that by engaging with Arendt's 'warning,' we can better recognize the subtle encroachments on our freedom and re-ignite a commitment to active citizenship, safeguarding our collective future from the quiet tyranny of conformity.

Totalitarianism Defined: Beyond Authoritarian Rule

To truly grasp Arendt's warning, we must first understand her unique delineation of totalitarianism. For her, it was not merely an extreme form of authoritarianism, but a distinct political phenomenon with its own terrifying logic. Whereas authoritarian regimes are characterized by dictatorial power, often maintained by military or socio-economic elites, they typically lack a coherent, all-encompassing ideology. They suppress dissent and demand obedience, but they don't necessarily seek to reshape every aspect of human life.

Totalitarianism, in Arendt's analysis, is different. It is defined by a charismatic leader, a fixed, pseudo-scientific ideology that claims to explain all of history or nature, and a relentless drive to exert absolute control over individuals and society. This ideology, whether rooted in race or class, aims to simplify complex realities into a singular, all-explaining narrative, often requiring the violent extermination of perceived enemies. Arendt argues that action, the highest realization of human potential through which individuals disclose their unique identities, is fundamentally suppressed in such systems. Totalitarianism, therefore, isn't just about governing; it's about fundamentally transforming human nature itself, reducing individuals to mere cogs in an ideological machine.

The Architecture of Control: Ideology, Propaganda, and Terror

How does totalitarianism achieve such pervasive control? Arendt identifies a chilling interplay of ideology, propaganda, and terror as its foundational mechanisms. The ideology serves as the movement's guiding principle, not only shaping its goals but also identifying and targeting 'objective' enemies. This 'monstrous logicality' justifies any means to achieve its predetermined ends. Propaganda, in turn, facilitates the internal cohesion of the regime, weaving a narrative that blurs the lines between fiction and reality, making the unbelievable seem self-evident.

Terror, however, is the ultimate tool. It's not merely used to suppress dissent; it eliminates the very spaces for free action and thought, creating an environment where citizens become complicit in their own subjugation through fear and confusion. The Leader, central to this framework, embodies the totalitarian movement, claiming personal responsibility for all actions. Their directives are often ambiguous, encouraging followers to interpret orders as they see fit, further entrenching the system of terror and complicity. This dynamic leads to a dangerous apathy, where individual agency is minimized, and civic responsibility dissolves into mass movements.

The most potent totalitarian control is achieved not through direct oppression, but through the cultivation of a widespread, uncritical conformity that stifles dissent before it can even articulate itself.

– Hannah Arendt's

The Fading Public Sphere: Sociological Roots of Compliance

Arendt’s analysis extends beyond the visible mechanisms of control to the deeper sociological implications of totalitarianism. She observed that the erosion of traditional social classes and institutions, which once provided frameworks for individual identity and collective action, could diminish the sense of community and solidarity essential for a healthy civic engagement. When these societal bonds weaken, individuals become isolated, losing the platforms necessary for critical discourse and collective opposition. This vulnerability makes them exceptionally susceptible to manipulative totalitarian tactics.

In such a fragmented society, individual identity becomes distorted, leading to a collective moral cynicism where people no longer believe in the possibility of meaningful resistance. The absence of an active public sphere, where citizens can deliberate and act in concert, leaves a vacuum that totalitarian ideologies eagerly fill. Historically, Arendt pointed to the aftermath of World War I and subsequent revolutionary upheavals as creating just such an environment – a lack of social stability that allowed 'mob' elements, previously marginalized, to be exploited by radical ideologies. This context highlights how societal breakdown creates fertile ground for conformity and the subsequent rise of totalitarian tendencies.

Historical Shadows: Nazism, Stalinism, and the Peril of Complicity

Arendt's theories were, of course, forged in the crucible of the 20th century's most devastating totalitarian regimes: Nazism and Stalinism. These historical examples vividly illustrate how totalitarian ideologies can redefine human collective identity, manipulating societal structures and undermining traditional political authority. In both cases, ideology (race for Nazism, class for Stalinism) served as the supreme arbiter, justifying total terror and the reordering of society toward a preordained end.

The Nazi genocide, for instance, exposed the profound complicity within German society. Widespread reluctance to acknowledge or disclose knowledge of the atrocities contributed to a pervasive culture of denial, stemming from fear, trauma, and a collective shame. This silence, Arendt suggests, is a form of ordinary conformity that allowed the unthinkable to become normalized. Similarly, Stalin's regime, despite claiming to pursue a modern legal order, prioritized ideological objectives over individual justice, employing mass terror even in the pursuit of 'legality.' These examples underscore the perilous danger of ordinary conformity in the face of radical ideologies and serve as a stark reminder that vigilance is crucial to prevent history from repeating itself in new forms.

The Digital Panopticon: Surveillance, Algorithms, and the New Totalitarianism

Arendt’s insights resonate with unsettling clarity in our contemporary landscape, particularly concerning technology and the erosion of political freedoms. She foresaw how technological advancements could reshape human identity and societal interactions, leading to what she termed a 'waste economy' where private life increasingly becomes public, and intimacy is compromised by constant surveillance. This perspective aligns powerfully with modern critiques of surveillance capitalism, where corporate interests exploit personal data to control individual behavior and societal norms.

Perhaps the most salient contemporary application of Arendt’s warning is seen in systems like the Chinese Social Credit System. Critics describe it as a manifestation of digital totalitarian control, exemplifying intrusive state surveillance and behavior modification. While proponents argue it fosters societal order, opponents contend it creates a repressive regime that stifles dissent and enforces conformity, reflecting Arendt's warnings about the dangers of unexamined compliance in modern governance. This system, I believe, represents a profound challenge to individual autonomy and civil liberties, pushing us to ask difficult questions about the price of convenience and control in the digital age.

The true danger lies not in overt tyranny, but in our quiet acquiescence to systems that subtly diminish our capacity for independent thought and action. It is precisely this potential for ordinary conformity to morph into a new form of totalitarianism that underscores the paramount importance of active participation in political life, as Arendt so powerfully articulated.

Reclaiming Our Agency: Action, Discourse, and the Lived Reality of Freedom

If totalitarianism thrives on conformity and the suppression of action, then freedom, for Arendt, is not an abstract ideal but a lived reality that necessitates ongoing action and discourse. She observed that political action, genuine deliberation, and shared initiative are crucial for a vibrant public sphere. However, Arendt also recognized the challenges to this ideal, noting how genuine political discourse can be subordinated to mere administration and consumption, leading to a climate where social media often amplifies polarization rather than constructive dialogue. Her concern about 'downshouting' – the suppression of debate and dialogue – feels particularly resonant today.

To counteract these forces, we must reclaim our agency. This means cultivating critical thought, engaging actively in civic life, and resisting the allure of apathy and unquestioning consensus. It demands a commitment to fostering spaces where diverse voices can be heard and where collective action is possible. As Arendt reminds us, the very fabric of democratic society depends on our willingness to question, to speak out, and to act, even when it is uncomfortable or goes against the prevailing current.

The sad truth is that most evil is done by people who never make up their minds to be good or evil.

– Hannah Arendt

The Echoes of Controversy: Engaging Arendt's Critics

Arendt's work, particularly her reflections on totalitarianism and the role of individuals within it, has not been without controversy. Her portrayal of Jewish leaders during the Eichmann trial, for instance, ignited significant debate, leading to accusations of insensitivity and misunderstanding of historical context. She suggested that their passive acceptance of the Nazi regime bore some responsibility, a point that understandably provoked strong reactions from many, including Jewish intellectuals.

However, Arendt consistently emphasized the need for a nuanced understanding of the events she analyzed, arguing that many criticisms stemmed from misunderstandings or political motivations. Scholars continue to celebrate her work for its interpretive richness and capacity to provoke critical thinking, cautioning against oversimplifying her complex arguments. Her assertion that violence often presupposes power, rather than the other way around, challenges dominant narratives and invites deeper exploration into the conditions necessary for democratic engagement and resistance to authoritarianism. Engaging with her critics, therefore, only reinforces the depth and enduring relevance of her insights into power, morality, and human action.

Beyond the Warning: Cultivating a Resilient Polis

Hannah Arendt's warning about ordinary conformity is not a tale of inevitable doom, but a profound call to vigilance. Her work compels us to look beyond overt acts of tyranny and recognize the more subtle, insidious forces that can erode our freedoms from within. We have explored how her distinctions between authoritarianism and totalitarianism, her analysis of control mechanisms, and her insights into historical complicity offer a chilling framework for understanding our present moment.

As we navigate an increasingly complex world—one shaped by technological advancements that blur the lines between public and private, and by digital systems that incentivize conformity—Arendt's insights are more crucial than ever. The choice before us is clear: to remain passive, allowing the quiet creep of conformity to define our reality, or to embrace our capacity for active citizenship, critical thought, and courageous action. Only by doing so can we cultivate a resilient polis, where freedom is not merely an abstract concept, but a vibrant, lived reality that we collectively safeguard and defend, one independent thought and action at a time.

Yes! The "banality of evil." I was thrilled when I saw your post. I wrote in my post yesterday that Kant's Radical evil was a prelude to her writings.

Several in Arendt's era came to a disturbing set of conclusions:

Milgram showed we’ll obey.

Zimbardo showed we’ll imitate.

Arendt showed we’ll normalize.

Hannah Arendt didn’t run experiments. She watched Adolf Eichmann on trial for Nazi war crimes and saw a man who wasn’t a demon, just a bureaucrat. He was ordinary and thoughtless — and responsible for organizing the plan of the holocaust.

I don't typically point out my own posts in my comments, but this one is a great combination.

https://frankgeorge8675309.substack.com/p/caution-magas-5-evils-are-contagious

Great post!!! She is absolutely correct! I’m surprised I’m not familiar with her or her work. It looks like I have some homework to do and a few key people to share a link with. Thank You!!! Oh and subscribe….